Greece and its lenders appear to be on an inexorable path to a Greek default unless Greece capitulates in the next few days. In a move meant to tell Greece that the onus was on them to offer more concessions, the IMF negotiating team left for Washington, as other senior European officials, such as Bundesbank chief Jens Weidmann and European Council president Donald Tusk issued warnings.

The gap between the two sides on the structural reform hot topics of pension and labor market reforms has seemed for some time too large to possibly be surmounted. Moreover, even though the creditors have clearly rejected debt renegotiation as part of the bailout, making it clear that they planned to address that only after a reform package was settled, Greece has continued to try to get it on the table, including it in its 47 page document submitted a week ago Monday, as well as providing a memo along with its response to the five-page document provided by the creditors last week.

This week, the media reported that European commission president Jean-Claude Juncker and Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem made an additional offer the week prior that Tsipras rejected, that of extending the bailout till March 2016 if the Greek government agreed now to certain structural reforms (press accounts varied as to how much Greece would have o concede to get the additional time; it was also not clear if this was a trial balloon or formally authorized).

Recall that after Tsipras received the creditor offer and met with Juncker and Dijsselbloem on Wednesday, he’s said he’d send a response by Thursday that would serve as a basis for another meeting to continue negotiations with Juncker on Friday. Tsipras instead cancelled the Friday meeting (and in keeping did not send a document) and went to Athens to give a speech to Parliament on Friday evening, in which he rejected the creditor offer with considerable vehemence.

I looked at both the Greek and creditor proposals last week and am embedding them below. The press did not discuss them much beyond flagging key points where the two sides remained at odds, for instance, on the remaining gap on the level of primary surplus and on the still large difference on pensions and labor market reforms; one of the more detailed accounts, at Bruegel, noted: “Pension reform: remains a red line for both sides….Labour market reforms: are probably the most red among the red lines at the moment.”

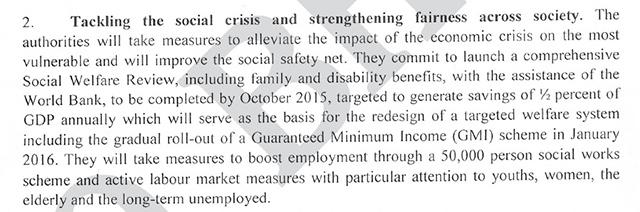

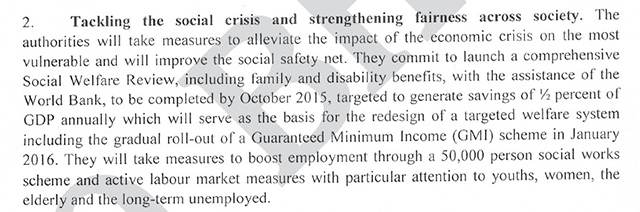

Consider this item on the first page of the creditor missive. It’s item 2, which one would think means the creditors wanted to make it prominent:

The creditors are proposing a social safety net and a minimum guaranteed income program, plus the hiring of 50,000 people for social works. Now a lot of pixels have been spilled on the Greece/creditor negotiations, far too many for me to stay on top of them all. Nevertheless I don’t recall seeing anyone take note of this section.

There’s no corresponding item in the Greek proposals, nothing even close. The Greek proposal, on pages 13-18, discusses “social security issues”. That’s what the media and the creditors have been calling pensions. The difference in nomenclature reflects how pensions have come to serve as an umbrella safety net in Greece. While other European economies have other forms of social welfare, like unemployment insurance, in Greece, pensions are the mainstay of social support. As the Economist pointed out in 2010 on Greek pensions:

Finally, as in many Mediterranean countries, all social spending was skewed towards pensions, essentially for vote-winning purposes. Things like unemployment benefits are pretty miserly in Greece, the real money has always gone to pensions, which have been used as a “substitute” for other welfare policies.

Now in fact there are enough underage people on pensions in Greece to make Germans see red. As reader IsabelPS pointed out, quoting Greek Reporter:

On Greek pensions, from December 2014 and the previous Labor Minister:

“In the public sector, 7.91% of pensioners retire between the ages of 26 and 50, 23.64% between 51 and 55, and 43.53% between 56 and 61. In IKA, 4.44% of pensioners retire between the ages of 26 and 50, 12.83% retire between 51 and 55, and 58.61% retire between 56 and 61. Meanwhile, in the so-called healthy funds, 91.6% of people retire before the national retirement age limit,” Vroutsis said.

So the seemingly high Greek pensions are due in part to an aged population, in part due to the fact that some of the spending on people under normal retirement age might fall under disability or unemployment insurance in countries with a more robust set of programs.

With that understanding, read the creditor offer that we flagged again:

I paarse the long second sentence, the one that begins, “They commit to launch a comprehensive Social Welfare Review” as saying: “You will get savings from current programs like family and disability benefits to round up 1/2% of GDP to fund a targeted welfare program that will include a Guaranteed Minimum Income scheme.” So far that does not sound all that interesting, since it is taking an bunch of current programs and using them to fund a bigger, simpler, and hopefully more equitable program. Not terrible, but it seems hardly important enough to feature in a short, high level document.

But this bit suggests there could be more to it: “which will serve as the basis for a redesign”. That seems to leave the door open for it to be funded more generously. Now mind you, the creditors have taken the view on part of the pension negotiations that Greece could preserve some of the benefits if they found a way to fund them. And regardless of what you make of that sentence, the social works program to hire 50,000 is above and beyond that.

Now this is all seems moot now, but was this a creditor attempt to find a path out of the Greece/lender impasse on pensions? As we’ve stressed, the pensions issue is such a hot button politically in creditor countries, due to the perception that they are generous. That means it’s impossible to get the needed Parliamentary approvals to unless they are reduced, particularly given what were seen as early retirement abuses. Were the creditors trying to give Syriza a channel for telling voters that the cuts in pensions would be offset by spending in new programs?

As we’ve said, the bigger problem was that the ruling coalition conceded on a key point early, that of maintaining primary surpluses, which are tantamount to austerity and agreeing to the painful target of 3.5% of GDP starting in 2018. Thus having conceded the point, they need to make the numbers at least appear to work. So even if that language was means as a channel to provide for programs to make up for what was lost on the pension side, Greece would still need to find a way to fund it within the stringent primary surplus targets.

A colleague with close contacts on the Greek side confirms that it’s worth questioning whether this idea was explored. But we seem to be well past that point, with both sides locked into a lose-lose strategy. But Greece is just about certain to suffer much more serious damage.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.