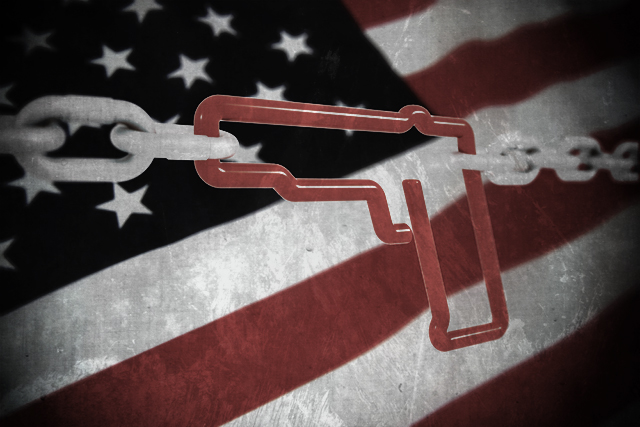

This week, I saw a statistic that made my skin crawl. It was one of those numerical comparisons that makes perfect sense when you see it but also causes a shudder or two when you grasp its full meaning. According to numbers pulled from various sources, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more Americans have died as a result of gun violence here in the United States since 1968 than have died in all US wars combined. When one considers the enormity of the bloodshed that has occurred over the course of US conflicts, the extremity of this internal violence is indeed quite staggering.

The Vietnam War sparked one of the most potent social movements of the last century and inspired connections between evolving movements. The tragedy of the Civil War – which pitted “brother against brother” – has been the subject of countless books and films, with many going so far as to romanticize the bravery of those whose fight was ultimately waged in defense of slavery. We marvel at the horrors of war, dramatize them and perpetually claim to learn from them, but we allow the horrors of our own culture to fade into the realm of the mundane. Barring a headline-worthy statistical anomaly that allows for the use of sensationalist language like “epidemic” or “crime wave,” our attention is rarely roused by everyday violence in the United States.

Occasionally, however, a spectacle of violence manages to grab our collective attention.

The gunning down of two Virginia journalists during a live news broadcast on Wednesday did just that. Like many victims of violence, Alison Parker and Adam Ward were simply going about their daily lives when they were struck down by gunfire. Their deaths hit some Americans especially hard because, as viewers and consumers of media imagery, they weren’t expecting it, either. Most Americans only hear or read about gun violence. They are removed from the day-to-day reality of it and spared the role of witness.

The striking exception to our common exemption is, of course, the commonplace publication of videos and images of police violence inflicted upon Black people and other people of color. But many also avoid those images or regard them as irregular, or worse, as an unfortunate consequence of the maintenance of law and order.

But to see violence up close, not uncovered or exposed in the pursuit of justice, but brandished on social media by the killer himself, made many feel as though they had been roped into the position of bystander. And they were. But what does this say about us as a culture, that we treat something so common as something utterly extraordinary?

When Hillary Clinton was recently called out by Black Lives Matter activists for her complicity with the expansion of the prison industrial complex – an expansion that has only fueled greater harm in Black communities – Clinton garnered a great deal of attention by telling the activists, “I don’t believe you change hearts; I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate.” Clinton went on to stress that if the activists only succeeded in changing hearts, “We’ll be back here in 10 years having the same conversation.”

The problem with that logic, of course, is that laws have been changed over the course of social movements, and we’re still back here having the same conversations. Laws are broken and bent backward over time when culture fails to change with them. Rules are disregarded or unraveled by insidious policy changes such as voter ID laws.

When it comes to violence, Clinton’s theory of changing laws rather than hearts has already proved false during her own time in politics. Three-strikes laws and mandatory minimums were championed by the Clintons during Bill Clinton’s presidency, but as we have seen over the course of prison expansion, stiffer penalties don’t make for safer communities. It’s not surprising that policy makers are attached to the notion of their own relevance – the idea that the world can be rewritten by the legislation they author and promote – but the world has a way of disregarding and undoing any change it’s not ready for, and that is a difficult reality for any policy maker to swallow.

Now, in the wake of Wednesday’s shooting, many on the left are discussing gun control. While I understand the intentions of such conversations, most fail to address the root issues at work. Why is it that violence is so inevitable in our country? Is it because we have access to guns, or is it because we are so attached to them? Both American pop culture and our manner of appreciating history indicate that gun violence is something that we simply can’t stop consuming. And when has illegality ever curbed the destructive habits of any population?

In reality, most of the measures that liberals push for at a legislative level wouldn’t keep guns out of the hands of most high-profile killers. But intensifying the aims of those would-be legislative cures wouldn’t curb our collective habit either. There is something deeper at work that manifests itself in the hands of Americans who pick up loaded weapons. But our problem-solving skills have been limited by the logic of politicians like Clinton, who sells quick fixes for cultural problems – fixes that never seem to work.

Many are also talking about mental health in the wake of Wednesday’s shooting. And while a lack of resources for those with mental illness is a very important topic, these conversations tend to follow a similar pattern to those that center on gun control in the wake of tragedy. The daily suffering of people with mental illness who have been denied resources – mental anguish, self-medication, homelessness and suicide – fade into the mundane in the United States, while a violent man with a gun conjures arguments about mental health being important because, well, without it, people with mental illness might kill us, or so the notion goes.

The fact that people who are mentally ill are much more likely to be victims of violence than to commit acts of violence is, of course, completely lost in these dialogues.

We don’t talk about creating a culture that cares for its own because they are deserving of care, or about how our treatment of vulnerable people is a reflection of our humanity. We don’t talk about why our culture is grounded in a romanticization – and in fact, a sexualization – of gun violence. Instead, we argue about laws when extreme circumstances unfold. And when the noise dies down, we return to accepting the mundane.

Hillary Clinton was wrong. What’s needed is a culture change. No policy or law can save us from ourselves. No amount of criminalization has prevented us from killing ourselves in greater numbers than any foreign enemy ever has, and no policy or law ever will. Hillary Clinton missed an important opportunity when she talked down to those young activists. She was talking to a group of people from a community deeply affected by violence, to whom suffering has not become mundane. She was hearing an honest analysis of the part she had played in making the world such as it is, and she was being given the opportunity to have an honest dialogue about how we can dismantle the ugliest aspects of our culture. Clinton passed up that opportunity, but the rest of the country doesn’t have to.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.