As Congress deliberates the revision of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, better known as “No Child Left Behind” and widely referred to by frustrated teachers and parents as “No Child Left Untested,” Education Secretary Arne Duncan has announced he will step down in December 2015. According to The Washington Post, during his six-year tenure, Duncan is reported to have largely bypassed Congress to “cajole and pressure states to enact policies, such as teacher evaluations and higher academic standards, that angered both teachers unions on the left and small-government conservatives on the right, dramatically expanding the federal role in education.” According to President Obama, “He’s done more to bring our educational system, sometimes kicking and screaming, into the 21st century than anyone else.”

The weakening of the public sphere in US education, painful as it is, is minor compared to recent developments in Mexico.

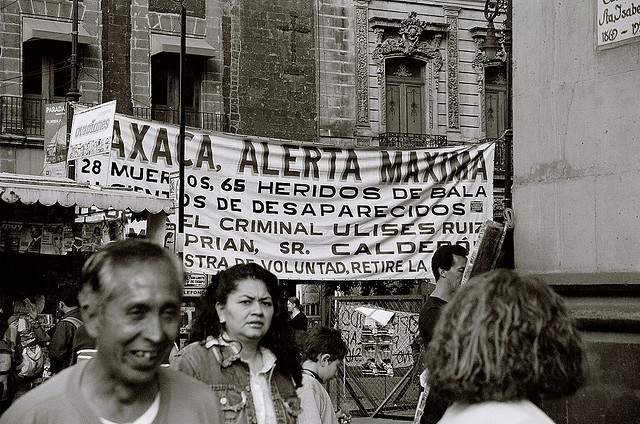

The weakening of the public sphere in US education, painful as it is, is minor compared to recent developments in Mexico. For nearly two years, tens of thousands of Mexican teachers have mobilized against so-called “education reforms,” especially in the southeastern Mexican state of Oaxaca, though virtually nothing of this massive teacher movement has been reported in mainstream US media. In Oaxaca and beyond, protesting Mexican teachers have demonstrated, gone on strike, seized buildings, closed highways and confronted the police and army, mainly nonviolently. According to the reformist teacher union movement (the CNTE), the “education reforms” imposed by President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration have nothing to do with educational improvement and everything to do with an aggressive neoliberal political agenda, the privatization of schools and attacks on hard-earned labor union rights and protections.

Since Mexico’s midterm elections last June, Oaxaca and several other Mexican states have endured massive militarization by federal troops. The elections served as a convenient pretext to heavily militarize states, especially Oaxaca, in order to repress teacher mobilizations against the imposed federal education reforms and union-busting aggressions. The only significant coverage to break the virtual silence across all US media was published by Truthout on August 1.

On July 27, 2015, as many as 10,000 armed Mexican federal and state police patrolled the streets of the state capital, also called Oaxaca, and nine federal police helicopters ominously traversed the city’s skies. The justification given by state authorities for this massive militarization was “to protect public safety.” In a state where, by government statistics, the percent of those living in poverty increased from 61.9 percent in 2012 to 66.8 percent in 2014, and those living in extreme poverty increased from 23.3 percent to 28.3 percent during these same two years of the Peña Nieto administration, the imminent danger that triggered this massive militarization was simply fear – fear of activist teachers legally and collectively denouncing multiple antagonistic actions taken by the government against the teachers’ union and its power over education in Oaxaca by putting their bodies in the streets.

Oaxaca’s teachers’ union, Section 22, an 83,000-strong powerhouse in the reformist, democratizing branch (CNTE) of the national teachers’ union (National Syndicate of Education Workers, or SNTE), had amassed its members for a mega-march in the city on that day. The protesting Oaxacan teachers were reinforced by contingents of CNTE teachers from other Mexican states, as well as parents, teacher education students, members of social organizations and the parents of the 43 students from the teacher education school at Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, who were “disappeared” in September 2014. The State Highway Patrol reported that approximately 15,000 protesters participated in the mega-march. Unofficial estimates were between 25,000 and 35,000. All say the response was enormous, yet peaceful.

One of Section 22’s major demands was to reinstitute union leadership in the State Institute of Public Education of Oaxaca (IEEPO), an institution that Oaxaca Gov. Gabino Cué had dismantled without consultation a week before. He immediately reorganized the IEEPO to intentionally exclude participation by teachers in order to terminate Section 22’s government-negotiated contractual power over vital aspects of education leadership in the state. Shortly thereafter, the government canceled the CNTE’s bank accounts, blocked their radio channel and issued arrest warrants for 32 union leaders in the state of Oaxaca.

A second demand was to halt implementation in Oaxaca of the federal “education reforms,” especially standardized testing of both new and veteran teachers, denounced by the CNTE as part of a corporate agenda that abrogates longstanding contractual agreements between the union and the government.

“This is not an education reform as much as it is a labor reform; what they want is for the state to stop offering free and public education,” said Dolores Villalobos, a teacher and member of the Section 22 teacher union.

A third demand was to approve a new education law for the state that had been drafted with union, community and legislative participation.

Bishop Raúl Vera, nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012, told Truthout that militarized repression of Mexican popular protest is on the rise, aided by US funds.

“The government does not defend the people; it defends itself … so that transnational investments can continue to advance in education, energy, petroleum resources, mining and other sectors,” Vera said in an interview.

The corporate synergy is astounding. Whether through self-censorship or power politics, Mexican mainstream media outlets totally support the government and corporate policy.

Incessant media coverage proclaims that the teachers’ union resistance is broken and the federal education reforms are marching ahead even in Oaxaca. From inside the “new” IEEPO, critical voices report that many new employees, some employed from other Mexican states, support the federal reforms, and only a minority prioritize accommodating federal reforms to the impoverished, indigenous population of the state.

Despite threats, militarization and state repression in Oaxaca, things have not gone as the government intended.

However, veteran voices from Section 22 report a different reality on the ground, as teacher union resistance continues in subtle but unrelenting ways. The “new” IEEPO is barely functioning, they say, as the bureaucrats appointed or imported by the governor have no idea how to run a school system. And while initially rank-and-file teachers were very fearful of the aggressive government threats of reprisals and physical violence, union fears now seem to be diminishing. Teachers are carrying out their teaching much as they did before, incorporating few if any of the imposed reforms.

Despite threats, militarization and state repression in Oaxaca, things have not gone as the government intended, and one of two outcomes are predicted to lie ahead: Either the government will have to intensify the repressions, or they will be obligated to negotiate with the teachers.

Suppression of information about teacher activism, repression and resistance in Oaxaca by US media conglomerates is equally disturbing. Failure to raise disquieting questions is a political act that condones rather than decries these aggressions.

But drastic policy shifts such as these, engineered by a worldwide network of corporations and the politicians who serve them, are not new. Nor is US political collusion with such heavy-handed international “reforms.” In 1973, the Nixon administration cooperated with the center-right-dominated Congress of Chile and overthrew the democratically elected Salvador Allende. The National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report (Rettig Report) determined that 2,279 people were killed for political reasons, 1,248 disappeared, 28,000 were tortured, at least 80,000 were imprisoned and about 200,000 fled the country for political reasons, according to Thomas C. Wright and Rody Oñate’s discussion of Chile in the Encyclopedia of Diasporas. What followed was a severe war on the public sphere marked by policies to privatize, deregulate and cut social spending. Designers of these policies were US and Chilean economic elites, most hailing from the University of Chicago’s economics department.

While the Chilean example today may seem like ancient history, the focus on corporate-triggered and government-imposed “education reforms” foists it into the present. In Chile then, as in Oaxaca today, education was one of the most affected sectors. The Chilean teachers’ union was dismantled, voucher plans were introduced, teachers’ contracts were privatized and privately managed schools received the same funding per student as public schools. Segregation increased as a result of privatization. The mainstream media were co-conspirators in the crime. Had we paid attention to the role of the US political and economic elite in Chile’s affairs throughout the 1970s and 1980s and acted, not only would we have been better able to ward off Chile’s catastrophe, but also we might have better anticipated and organized against the corporate educational stampede that would engulf the United States and be exported to so many other contexts.

But resistance continues among activist teachers, not only in Oaxaca. We remember the experiences of teachers in Wisconsin, and the re-emergence of the teachers’ union movement in Los Angeles, Portland, St. Paul and Chicago. We recognize the profound struggles of teachers and parents today against high-stakes testing across the United States and ponder the perils of not engaging their voices in the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. We also ponder the possibilities of how much more powerful teachers and their allies could be if we would recognize our shared experiences and open up new paths for cross-border solidarity and action.

In Oaxaca, we are witnessing a form of contestation to the corporate agenda in education that includes teachers, students and the public. Despite media misinformation or silence, the resistance is sustained and so far nonviolent. Resistance to the corporate stampede in the United States has been far too insular. We must understand, following Oaxaca’s example, that this is not merely an issue for and about teachers. It is about all of our children and the quality of their public school education. It is not teacher activism and organizing that endangers our freedoms, but rather the silencing of information and serious debate and legitimate protest about a matter as crucial as the education of our children.

Note: Bess Altwerger, Rick Meyer, Becky Smith and Jose Soler also contributed to this article.

Bess Altwerger is co-chair of the Save Our Schools National Action Committee.

Rick Meyer is co-chair of the Save Our Schools National Action Committee.

Becky Smith is a board member of Save Our Schools and steering committee secretary.

Jose Soler is a steering committee member of Save Our Schools.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.