The following is an account of Todd Lewis Ashker’s efforts — on behalf of both himself and other prisoners — against solitary confinement at the infamous Pelican Bay State Prison in California.

A Tale of Evolving Resistance

In 2013 the call for the largest coordinated hunger strike in American history came from the Pelican Bay Short Corridor Collective, a political alliance between the twenty “main representatives” of the prison racial groups. Ashker is one of these representatives, along with Arturo Castellanos, Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa (aka Ronald Dewberry), and Antonio Guillen. The four also published a joint letter calling for the cessation of all hostilities among racial groups. The strike lasted sixty days and was joined by thirty thousand people, a quarter of the state’s prison population, garnering significant global attention. Ashker has successfully sued the prison system at least fifteen times — earning people in prison the right to hardcover books (with the covers torn off), limited mail correspondences with individuals held in other facilities (his father is also incarcerated), and the right to keep the interest generated from prisoner accounts. Ashker was one of the lead plaintiffs in the class-action lawsuit filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights, Ashker v. Governor of California, which reached a ground-breaking settlement on September 1, 2015, that promises to significantly scale back the use of solitary confinement in Calfornia’s prisons. According to the terms of the settlement, CDCR can no longer hold prisoners in isolation indeterminately or for more than ten years. In addition, “gang validation” is no longer a legitimate reason for placement in the SHU. As a result, an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 prisoners may qualify for release into the general population, including the 500 that have been isolated at Pelican Bay for over ten years. Ashker will be placed in a high-security unit where he’ll able to interact face-to-face with other prisoners for the first time in twenty-five years.

Hell Week

I’ve now spent more than twenty-seven years in solitary confinement, aka Security Housing Units (SHU). My original six-year term started in 1984 and was eventually increased to twenty-one years to life. I’ve been personally subject to and/or witnessed almost every form of abuse imaginable. This is a summary inclusive of my evolving resistance and fight for human rights.

It was at Folsom State Prison that I learned that prison staff are the real enemy. Guards are far more prone to dirty, illegal moves than any convicted felons I’ve ever done time with. By “prison staff” I’m referring to custody, medical, and even the “free” staff, like plumbers and electricians. Top to bottom, they’re all corrupt.

The staff at Folsom State Prison used to play different racial groups against each other by setting up yard incidents. They’d break up the fights by firing live rounds from their Mini 14 assault rifles into the crowd. In 1987 they encouraged the Africans to attack the whites and vice versa. During one incident, they shot my friend in the stomach, then planted weapons in the drain they later claimed were used in the melee. A guard was stabbed in the neck a few days later.

About a week later, a large group of staff took a group of us out of our cells, twenty whites and four Africans. We were then escorted one at a time with our hands still cuffed behind our backs, in nothing but our boxers and shower shoes, to a secluded area where they beat the crap out of us. They told us they were going to kill us and bury us behind the prison. I ended up covered with my own blood from head to foot, with a broken foot, cracked ribs, and my teeth through my lip.

As the guards escorted us to the medical clinic, one asked me what I was smiling about. “Well, for being killed and buried I feel pretty good,” I replied. The sergeant told the guards to put me through another beat down for that crack. When what staff referred to as “hell week” was finally over, twenty-four prisoners were charged with assaulting staff. Not one guard suffered any consequence.

I was placed in one of the new Bedrock SHU cells as soon as the cement dried. We each were allowed to have a shoebox-sized amount of property, no shoes, no access to canteen and only half our food rations. We responded with a minor “dirty protest,” each of us filling milk cartons with shit and piss, then slinging them all over the control booth windows every time we’d come out for showers. After about two weeks of having to clean up shit every day, staff began giving us our full food ration, plus extras.

The Roman gladiator pit–style fights sadistic guards set up continued at Bedrock. The Bedrock unit looked like a ward in a military hospital — men with “dead” arms and legs from nerve damage, others with colostomy bags, and one missing an eye. At least two men were shot and killed. The guards filed charges against us for these injuries, using the incidents to further the guard union’s agenda — more supermax prison cells!

Within the first nine months in Bedrock, half the men there became “debriefers,” informing on other prisoners to get out of there and into protective custody. Either you break, or you do all you can to survive.

Pelican Bay SHU

While at New Folsom SHU, on May 25, 1987, I entered a guy’s cell for a prearranged fight. He’d challenged me to a fistfight to settle some fabricated beef. I had to accept; it was that or request protective custody, which I’d never do. His cellmate immediately placed a mattress over the door to block the control booth’s view, hoping to keep the guards from shooting blindly into the cell.

The guy swung at me with an eight-inch knife. As we fought over it, two guards fired a total of three rifle shots through the mattress. The guy ended up stabbed, and took a bullet in his shoulder. He died an hour later at the outside hospital.

In California, if you’re put in the SHU for killing someone, you get sent there for a maximum of three to five years. If you’re a validated gang member, you can count on spending the rest of your life in the SHU. After I was validated, I was transferred from New Folsom SHU to Pelican Bay SHU on May 2, 1990. Upon arrival I was told by staff that the only way I’d ever leave was to parole, die, or debrief.

A few months later the control booth opened my cell door when a prisoner was on the tier who they’d allegedly overheard threatening me two days before. With the alarm blaring and eight or ten guards screaming “Shoot them” at the control booth, the two of us began exchanging blows. The guard shot me from about nine feet away. The bullet hit my right radius about one inch above the wrist, disintegrating more than two inches of the radius, and broke the ulna into ten separate pieces. My hand was barely attached to my wrist by a bit of muscle and skin.

At this time prison staff were desperate to fix a serious flaw in the cell-door security system. The state had just spent more than $217 million on Pelican Bay and staff needed to have documented support to accompany any request for additional emergency funds. Toward this end, they falsely claimed I’d opened my cell door myself.

After being shot, I spent five days in the outside hospital. The nurses were kind. For the first time in more than six years, I was treated like a human being. I had completely forgotten what that felt like.

Evolving Resistance

During my first few years of imprisonment, the only way I knew how to deal with the abusive conditions was violent resistance. For more than two decades, we’d all watched the guards successfully pit racial groups against each other to the point where being on “lockdown” was a common state of affairs. “Lockdown” means everyone is kept in his or her cell 24/7 without yard time or programing. It means higher security and more guard jobs and higher pay. It is in the interest of the guards’ union to have violence in the prisons, resulting in more jobs, more dues-paying members, more political power in the state. This is all fodder for the fascist police state mentality that plagues our country today.

Part of the torture I’ve personally experienced during the past twenty-nine years of solitary confinement has been the repeated denial of adequate medication for the chronic pain in my permanently disabled arm. Adding insult to injury, staff periodically remind me that I “hold the key to get out of the SHU and receive better care for my arm . . . by debriefing.”

In the late 1980s some of us in Bedrock started to recognize that the prisoner class was getting the short end of the stick. We decided to learn the law and use the legal system to rein in the California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR) illegal and abusive policies. From 1988 to the present I have been challenging prison conditions in the courts. I have been a named plaintiff or assisted in several cases resulting in positive rulings beneficial to prisoners.

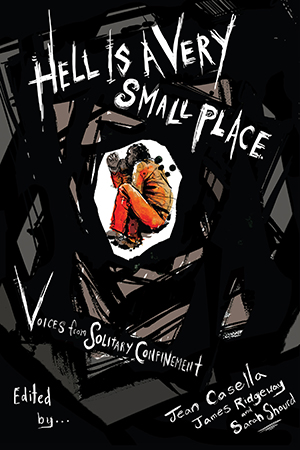

(Image: Molly Crabapple)The Short Corridor Collective

(Image: Molly Crabapple)The Short Corridor Collective

In 2006, they decided to isolate two hundred of the alleged “worst of the worst” prisoners at Pelican Bay into the “Short Corridor.” Fortunately for us, the prison’s definition of “the worst of the worst” includes many fine people. Many of us have been prison condition litigators and many are well read. All of us are long-term SHU prisoners who have been subject to the same type of torturous conditions for two or more decades. In the Short Corridor, we soon came to recognize and respect our racial and cultural differences. We shared reading material on history, culture, sociology, politics, etc. We came to recognize that we are all in the same boat when it comes to the prison staff’s dehumanizing treatment and abuse — they are our jailers, our torturers, and our common adversaries.

My good friend Danny Troxell was also moved to the Short Corridor. Danny and I began reading political books, including Thomas Paine, Naomi Wolf, and Howard Zinn, then we would discuss them across the tier. Six other men often joined in and the conversation gradually shifted to our progressively punitive prison conditions.

In 2009, we were introduced to a sociology professor named Denis O’Hearn, who invited Danny and me to participate in a class at Binghamton University. O’Hearn sent us the books that were required reading by the class, and asked us some questions related to our opinions on the subject matter. One of the books was Nothing But an Unfinished Song, about Bobby Sands and the Irish prisoner hunger strikes of 1980–81. This book greatly increased my awareness of and respect for the power of peaceful resistance against oppression.

At first many of us in the Short Corridor opposed the idea of a hunger strike. Yet, when we realized how it’d been used effectively in other parts of the world, we decided it might actually gain us the widespread exposure we needed to force an end to long-term solitary. We talked with other prisoners in our pod area and everyone agreed with the idea. That’s when the “Short Corridor Collective” was born and we articulated our five core demands. We spread the word via the grapevine about our plans to strike — making clear in our articles that no person or group was leading the protest and that this was to be a purely voluntary action.

In 2012 we wrote the Agreement to End Racial Group Hostilities, a call for a ceasing of violence between racial groups across the state. [See below.] Then in 2013 the hunger strike, combined with work stoppage, began — more than thirty thousand prisoners answered our call.

The prison administration portrayed the Short Corridor Collective as “violent, murderous gang leaders, making a power play to regain control of the prison system by forcing prisoners to hunger strike.” Despite this, I believe prison officials’ efforts to turn global support against us backfired. After sixty days we agreed to suspend the strike in response to lawmakers Loni Hancock and Tom Ammiano’s public acknowledgment of our issues and request for time to enable them to hold hearings and hopefully enact legislation.

We Hope the Tide Is Turning

We are not operating openly in a free system; we are in a protracted struggle against a powerful entity with a police state world view. It’s difficult to keep a movement together when we are so isolated, constrained, and surveilled at all times. CDCR counts on internal disputes and hopes for us to implode as a result of their increased pressure on us post–hunger strike. We all do the best we can.

We hope the tide is turning. Hundreds have been released to general population. That is a partial victory, but it’s not nearly enough. We have held on for so long that change sometimes seems unlikely. We’ve become skeptical of hope, but that may be because there is a possibility we might win. The reason for our progress is our collective unity inside and outside the walls and the global attention our cause has attracted. Our support remains strong, and continues to grow, while we patiently wait and see if change comes via our collective efforts inside and outside these walls.

It’s an honor to participate in our collective coalition. For the third time in twenty-nine years I have felt a sense of human connectedness.

This collective energy — inside and out — keeps us strong, positive, and alive. It gives us hope of one day having a glimpse of trees; feeling the warmth of the sun; receiving a hug, kiss, or handshake; sharing a game of basketball or checkers; tasting a hot meal that has flavor or feeling a bed that is warm.

We stand united as a prisoner class, not just for ourselves, but for those who are young and headed this way. I stand strong, united in solidarity with each of you.

Agreement to End Hostilities, August 12, 2012

To whom it may concern and all California prisoners:

Greetings from the entire PBSP-SHU Short Corridor Hunger Strike Representatives. We are hereby presenting this mutual agreement on behalf of all racial groups here in the PBSP-SHU Corridor. Wherein, we have arrived at a mutual agreement concerning the following points:

1. If we really want to bring about substantive meaningful changes to the CDCR system in a manner beneficial to all solid individuals, who have never been broken by CDCR’s torture tactics intended to coerce one to become a state informant via debriefing, that now is the time for us to collectively seize this moment in time, and put an end to more than 20–30 years of hostilities between our racial groups.

2. Therefore, beginning on October 10, 2012, all hostilities between our racial groups . . . in SHU, Ad-Seg, General Population, and County Jails, will officially cease. This means that from this date on, all racial group hostilities need to be at an end . . . and if personal issues arise between individuals, people need to do all they can to exhaust all diplomatic means to settle such disputes; do not allow personal, individual issues to escalate into racial group issues!!

3. We also want to warn those in the General Population that IGI will continue to plant undercover Sensitive Needs Yard (SNY) debriefer “inmates” amongst the solid GP prisoners with orders from IGI to be informers, snitches, rats, and obstructionists, in order to attempt to disrupt and undermine our collective groups’ mutual understanding on issues intended for our mutual causes [i.e., forcing CDCR to open up all GP main lines, and return to a rehabilitative-type system of meaningful programs/privileges, including lifer conjugal visits, etc. via peaceful protest activity/noncooperation e.g., hunger strike, no labor, etc. etc.]. People need to be aware and vigilant to such tactics, and refuse to allow such IGI inmate snitches to create chaos and reignite hostilities amongst our racial groups. We can no longer play into IGI, ISU, OCS, and SSU’s old manipulative divide and conquer tactics!!!

In conclusion, we must all hold strong to our mutual agreement from this point on and focus our time, attention, and energy on mutual causes beneficial to all of us [i.e., prisoners], and our best interests. We can no longer allow CDCR to use us against each other for their benefit!! Because the reality is that collectively, we are an empowered, mighty force that can positively change this entire corrupt system into a system that actually benefits prisoners, and thereby, the public as a whole . . . and we simply cannot allow CDCR/CCPOA – Prison Guard’s Union, IGI, ISU, OCS, and SSU to continue to get away with their constant form of progressive oppression and warehousing of tens of thousands of prisoners, including the 14,000 plus prisoners held in solitary confinement torture chambers [i.e., SHU/Ad-Seg Units], for decades!!! We send our love and respects to all those of like mind and heart . . . onward in struggle and solidarity . . .

Presented by the PBSP-SHU Short Corridor Collective: Todd Ashker, C58191, D1-119

Arturo Castellanos, C17275, D1-121

Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa (Dewberry), C35671, D1-117

Antonio Guillen, P81948, D2-106

And the Representatives’ Body: Danny Troxell, B76578, D1-120

George Franco, D46556, D4-217

Ronnie Yandell, V27927, D4-215

Paul Redd, B72683, D2-117

James Baridi Williamson, D-34288, D4-107

Alfred Sandoval, D61000, D4-214

Louis Powell, B59864, D1-104

Alex Yrigollen, H32421, D2-204

Gabriel Huerta, C80766, D3-222

Frank Clement, D07919, D3-116

Raymond Chavo Perez, K12922, D1-219

James Mario Perez, B48186, D3-124

Copyright (2016) of Todd Lewis Ashker, as included in Hell Is a Very Small Place: Voices from Solitary Confirnment. Not to be reposted without permission of the publisher, The New Press.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $47,000 in the next 8 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.