During a panel discussion this May on Community Choice Energy, a rapidly growing initiative in California and six other states that enables communities to seize control of local electricity services, I argued for the economic benefits of building out local, decentralized renewable energy assets such as rooftop and community solar arrays. I was followed by a panelist who chided my “misguided” belief in the virtue of locally-generated, clean energy.

“Who cares whether our electricity is locally generated?” he quipped. “I’ve never heard of anyone demanding local pants, and local electricity doesn’t make any more sense than local pants.”

The speaker’s rhetorical gambit was that “local pants” are the height of absurdity. In his worldview, the globalized economy is an immutable reality too successful and too entrenched to warrant reconsideration.

This mindset has clearly been dominant for decades, but its days are numbered. Bernie Sanders’ denunciation of “free-trade” agreements has traction because people in the US are finally realizing that cheap imports are the devil’s bargain.

Why Local?

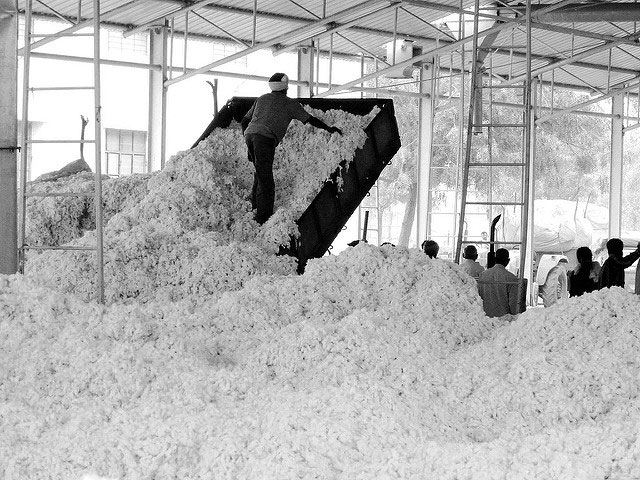

Take pants. Ninety-eight percent of them are made overseas out of fibers that travel 13,000 miles from farm to rack. Within two years of the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), North Carolina local apparel business owner Eric Henry was forced to lay off 86 of his 100 employees because he could no longer compete with multinational brands that rushed to offshore production. Those 86 jobs, and the health care and retirement benefits that went with them, are now performed by workers who make 26 cents an hour and labor under dangerous, sometimes deadly, workplace conditions.

Multiply Eric Henry’s story many tens of thousands of times and we’re looking at a global apparel industry that gluts the market with clothing that’s cheap for the customer, but has all kinds of hidden costs for the environment and for workers both here and abroad. So, would I prefer local pants to this unsustainable horror story? You’d better believe I would.

Localization enables us to live within the material and human limits of our bioregion rather than raiding the resources of other bioregions.

Though you won’t hear it on the evening news, the global economy is being strangled by a wicked knot of economic and environmental problems of its own making, including a century of marketing propaganda that has elevated material wish fulfillment above all other human endeavors. The global economy’s death spiral has been endlessly documented and foretold (to little effect), but consider just this one key indicator: One in three humans don’t have enough clean water, a situation that will affect half of humanity within 15 years.

I mention water because it happens to be the foundation for life on Earth as well as an essential ingredient for just about any business enterprise one can imagine, but we’re pushing up against all kinds of limits — oil, topsoil, fisheries, coral reefs, forests, pollinators, predators — you name it, and we’ve killed, damaged or squandered it.

What we have instead is lots of money on the ledgers of plutocrats and lots of stuff in garages and landfills. It’s surreal to have to state the obvious, but we’ve been so busy enjoying our 100-year fossil-fueled joyride, and so culturally conditioned to believe that humans’ mastery over nature is interminable, that we’ve failed to notice the wall rushing up to bash our skulls in.

Localization enables us to live within the material and human limits of our bioregion rather than raiding the resources of other bioregions as is the current practice, in which the global South serves as a labor and natural resource colony for its northern overlords (enabling us to postpone the day of reckoning our consumptive lifestyle begets). Re-localizing and re-decentralizing our economies are prerequisites for human survival on a hot, crowded planet with finite resources. To paraphrase James Hansen of NASA fame, we can either change our ways or they will be changed for us.

This doesn’t mean that every single item we consume must be manufactured locally. We might still, weather permitting, be able to import some commodities and specialty goods we can’t produce locally and are loathe to live without (chocolate immediately comes to mind). But we’d be well advised to spend the vast majority of our dollars on local businesses selling locally made products for a few very good reasons:

- Research compiled by the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (BALLE) shows that every dollar spent in a local business produces between one-and-a-half and four times the number of jobs as a dollar spent a similar nonlocal business. That’s because 47 percent of local business revenue recirculates in the local economy vs. 14 percent for chains, according to a 2012 national study by Civic Economics.

- Businesses are less likely to ruin their own homes. As Jared Diamond documented in Collapse, civilizations fall apart when the rulers are able to insulate themselves from the impact of their reckless decisions. Likewise, there’s plenty of evidence (much of it set forth in Michael Shuman’s book, Local Dollars, Local Sense) that nonlocal businesses have worse environmental track records than local ones. Not even the most foolhardy CEO wants a toxic mess in her own backyard.

- Local businesses tend to stick around. Because the owners and workers are rooted in the local community and lack the capital available to publicly traded corporations, they rarely offshore their operations. Their longevity provides employment stability and spares local governments the loss of millions of taxpayer dollars on consistently unsuccessful incentives to attract and retain nonlocal businesses.

- The global economy is as inherently unstable as a Jenga tower, with every enterprise in every part of the world directly or indirectly touching every other. It’s vital that we have at least the scaffolding of local economies in place before a tremor causes the whole damn thing to collapse.

As farmer and essayist Wendell Berry writes, “If the government does not propose to protect the lives, livelihoods, and freedoms of its people, then the people must think about protecting themselves.” Localization is an exercise of community power in the absence of governmental willingness to attend to the needs of the 99%.

Local Pants Matter

Let’s take a look at what a local pants enterprise would actually look like. Imagine a small, worker-owned pants enterprise. It churns out a relatively small number of pants made from locally available fibers and recycled textiles. It pays its workers a living wage, not a sweatshop wage, and this makes its pants cost a little more than pants from Target, but they’re not as expensive as you might assume because this worker-owned enterprise saves on shipping and marketing. And unlike Target pants, local pants are made to last and offer long-term value.

If they cost a bit more, that’s OK, because I, too, earn a living wage at the local bike shop. The higher price tag means that I’ll own fewer pairs (versus the 11 I’m ashamed to say are now hanging in my closet). When the pants start to wear out, I’ll mend them rather than buying new ones. Nor will I get rid of them when they start seeming unfashionable.

Sometimes I run into the people who made my pants and I thank them and we chat a bit and feel good about having a relationship; not anything terribly deep, but much more personal than the relationship I currently have with the Bangladeshi woman who sewed the label into my Levi’s.

All’s well in our local pants utopia until, one day, the zipper on my jeans breaks. The co-op takes responsibility for replacing the defective zipper because, otherwise, next time I see the co-op members at the farmers’ market, I’m not going to be so friendly and chatty, and then they’ll go home feeling bad. I don’t have to make a federal case out of it — they do the right thing because they’re my neighbors and it’s obvious to everyone that we’re all in this together.

If I really like my local pants co-op, I might even invest in it. When the co-op’s workers need to raise money to buy some new sewing machines, I might lend them the money for a small return. No one’s getting rich here — no CEOs, no shareholders, no Mad Men, no venture capitalists, no angels, no devils. The money I loan them and the money I pay them for my pants circulates in the local economy where it benefits all of us. The local pants worker-owners may want to get their bikes tuned up, and guess where they’ll come?

But wait, what about the workers across the global South who sew for transnational companies? Don’t they need jobs too? Is my localist ethic actually just parochial-minded trade protectionism that ignores the economic needs of the global South?

That accusation holds water only if we assume that countries in the global South can and should follow the same path to prosperity as the US and Europe did. But this is not remotely feasible. The United States and Europe polluted and exploited their way to prosperity with catastrophic outcomes for the environment and for the billions who struggle to survive in ecologically and economically brutalized regions of the world. There’s no one and no place left for the global South to exploit other than itself.

If we develop thousands of small and medium-scale solar projects on our own rooftops, then the economic benefits are multiplied and diffused.

Countries like Bangladesh, whose economies are based on garment exports, generate massive profits for multinational corporations, while their own people remain trapped in poverty. Were Bangladesh, instead, to produce local pants, along with local food, electricity and other necessities, it could move toward terminating its de facto colonial status and build a self-reliant economy; not materially rich by bloated US standards, but secure in its ability to meet its citizens’ basic needs. As long as I keep buying Bangladeshi-made Levi’s, I’m supporting a race-to-the-bottom arrangement that impoverishes Bangladeshis, displaces well-paid US workers and obstructs the creation of local, living, sustainable economies. Levi’s shareholders get rich, but to the detriment of everyone else. And the Bangladeshi export economy remains geared not toward local needs, but toward the fancies of foreign consumers.

The same goes, by the way, for electricity generation here at home. My co-speaker chastised me for being indifferent to residents of California’s Central Valley, who suffer unemployment rates twice that of the San Francisco Bay Area. Wouldn’t it be better, he argued, for the Community Choice Energy program in Alameda County, where Berkeley is located, to import utility-scale solar from the Central Valley rather than developing our own clean energy resources?

Well, no, it wouldn’t be better. For starters, significant waste occurs when electricity is transmitted across long distances, waste that an energy-constrained society can ill afford. Second, these huge solar projects take years to get approved and built (and for good reason as they’re typically located in fragile desert ecosystems).

To reject the imperative of re-localizing our economies requires a great deal of denial and/or hubris.

But more to the point here, centralized energy begets centralized profits. It’s a business-as-usual boon for huge energy corporations who exploit the lower labor costs of the Central Valley and swallow up whatever profits are to be made. If, instead of importing our solar power from one giant remote facility, we develop thousands of small and medium-scale solar projects on our own rooftops and parking lots, then the economic benefits are multiplied and diffused. The Central Valley can and should create its own Community Choice Energy program to enjoy the benefits of localism.

To reject the imperative of re-localizing our economies requires a great deal of denial and/or hubris, twin cultural delusions that are at the root of our existential predicament. We deny that the global model of endless growth and concentrated wealth is inherently unsustainable. And, to the extent that we acknowledge the environmental damage global capitalism has wrought, we arrogantly believe ourselves to be smart enough to mitigate whatever further environmental catastrophes are in store. Surviving ecological collapse … isn’t there an app for that?

Local pants may not be a good fit for people with supersized magical beliefs, but they look awfully good on the rest of us.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.