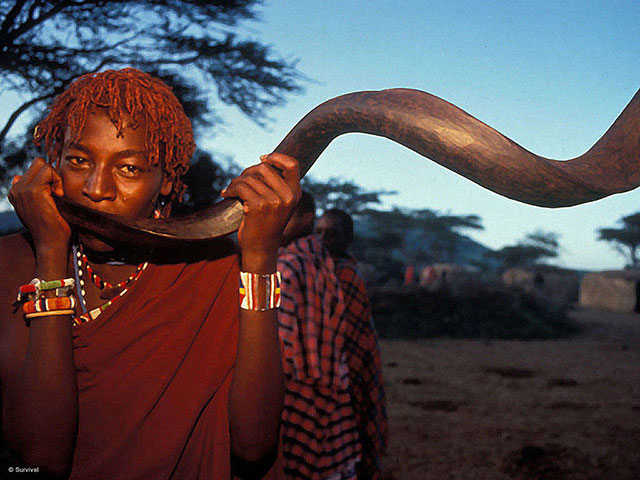

A Maasai Moran blows a kudu horn as a symbol of his coming of age in Kajiado, Kenya. The BBC’s new documentary *series* “The Hunt” juxtaposes unrelated shots of Maasai people with stock footage of lions to erroneously imply that the Maasai are in a “constant war” with the lions. (Photo: Survival International)

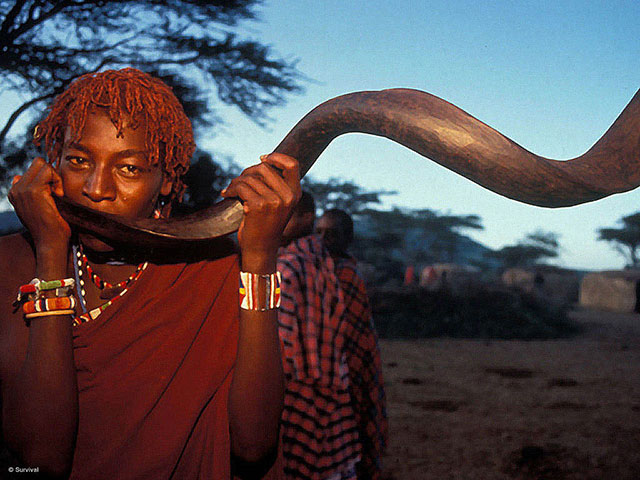

A Maasai Moran blows a kudu horn as a symbol of his coming of age in Kajiado, Kenya. The BBC’s new documentary *series* “The Hunt” juxtaposes unrelated shots of Maasai people with stock footage of lions to erroneously imply that the Maasai are in a “constant war” with the lions. (Photo: Survival International)

Over the last few weeks, BBC America has broadcast “The Hunt,” the latest offering from world-renowned natural history broadcaster David Attenborough. The formula is familiar: gorgeous photography, silky smooth voiceovers and tear-jerking narratives about the animals on screen. The series has profiled the world’s most “charismatic” predators — big cats, birds of prey, wolves, bears — and the ways in which they dominate their environment. The final episode focused on conservation and the threats faced by many of these species, which are unquestionably very serious.

Sadly, rather than critiquing poaching or industrialization, the program placed most of the blame for endangering species like the lion and the tiger on the shoulders of the tribal people who live in the so-called “wildernesses” that had been photographed. The narrative was full of distortion and misrepresentation and seemed to support an essentially colonial form of conservation that is deeply problematic.

Tribal peoples have been dependent on and managed their environments for millennia. Despite this, they were only cited at all as a threat to endangered flora and fauna. This attitude — assuming that Westerners know better how to protect the environment — is extremely widespread. It is also deeply neocolonial and has real consequences for tribal communities around the world.

The first section of the program focused on tigers in India. We saw them in their full glory, stalking deer in the forests of South Asia. For a long time, Indian tiger conservationists have claimed that to protect the Bengal tiger, it is necessary to create large reserves in which the tigers can live, breed and hunt.

There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong with this, until you consider the fact that hundreds of thousands of India’s tribal people (known as Adivasis) have lived in these reserves for generations. According to “The Hunt,” these people should be subjected to “voluntary relocation,” a process by which thousands of Adivasis across India have been harassed, bullied and bribed into leaving their land for lives of poverty and marginalization on the fringes of mainstream Indian society.

There is no evidence that tribal presence in reserves harms tigers. In fact, the reverse is true — evidence proves that tribal peoples are better at looking after their environment than anyone else. In the one reserve in southern India where tribespeople have been allowed to stay, tiger numbers have increased at above the national average.

Likewise, tribes are not responsible for the decline in tiger numbers. It is hunting — by the British colonial elite, by India’s upper classes and by others conspiring with corrupt officials — that has decimated the Bengal tiger.

Adivasis — many of whom revere the tiger and worship it as a god — are not to blame. But the simple logic of the relocation policy was recited in “The Hunt” almost as a mantra: “conflict is inevitable” but “as people move out, the tigers move in.” This sort of patchy treatment of a very serious issue was irresponsible and dangerous.

Krithi Karanth, an Indian conservationist interviewed for the program — who acknowledged problems around the evictions, but nevertheless continues to support them — claimed that it’s a question of “difficult choices”: “India’s changing very rapidly and sometimes you have to make difficult choices…. In some places it’s been done badly, but in others, it’s been done right.”

It isn’t the tribal people themselves who are making these fundamental decisions about their lives, but rather professional conservationists. Many of them are western-educated and work for big conservation organizations, such as (in the case of Karanth) the Wildlife Conservation Society (whose India program director is her father, K. Ullas Karanth). In many tiger reserves, tribal people have been frequently arrested and beaten. They are moved to inadequate camps away from their ancestral land and expected, as the narration said, to “fend for themselves.” Many receive only a small part of the promised compensation and few, if any, have thrived after “relocation.”

“The Hunt” features Karanth saying that Indian Adivasis living on their land have “a very difficult life…. Constantly living in fear of elephants, leopards and tigers…. People want to live in cities.”

In reality, however, many members of India’s Adivasi population express a desire to remain on their land. As one man, Lakanth Sing Barami, from the Baiga tribe, put it to a campaigner from Survival International, the human rights organization with which I work: “We are going to try and stay in this place…. How can we leave such great wealth behind? Do not uproot us.”

It makes no sense whatsoever to evict peaceful people from their ancestral land in the name of conservation. Tribal peoples feel a deep sense of connection to their land and its loss can be an existential matter to them. The promised compensation, or the chance to live in small breeze-block huts with gas and electric lighting, but no real economic prospects, does not change that.

One Adivasi man interviewed for “The Hunt” put it bluntly: “Better just to drop a bomb on us. Then they wouldn’t have to waste money on compensation.”

The program’s narrator did not offer any comment on this.

The show then moved on to another people in another part of the world — the Maasai in Tanzania. Long-time viewers of BBC wildlife shows will be familiar with the sweeping savannahs and majestic prides of lions, but here, the editors give us a different angle: tribal people engaged in what is described as a “constant war” with lions.

Never mind the fact that the sense of a “war” was created more or less entirely through creative editing, juxtaposing clearly unrelated shots of aggressive looking Maasai “warriors” with stock footage of lions appearing to run away in terror. Ignore the absurd claim that hunting rituals and occasional clashes between humans and animals constitute an “ancient combat.” Discount the shoddy logic of claiming that this has been going on for “2 million years,” but has only just now become a problem. The most worrying element of this section of the program was the bald-faced colonial attitude of the white American conservationists on the ground, seeking to lecture tribal people on what they can and can’t do.

Europeans have been interfering in Africa for centuries. Many justifications have been put forward for forcibly trying to dominate the lives of Africans, including justifications concerning religion, security, economic development, “progress” and “civilization.” Conservation, it seems, is rapidly becoming a new justification for this power dynamic.

Craig Packer — a famous American conservationist and interviewee for this section of the show — seemed to see no problem with driving around the grasslands in a jeep, telling Maasai people how best to look after their lands. Worse, he also proposed erecting electric fences across the savannah, separating people from wildlife. The historical connotations of this — dividing up a continent without local people’s consent — either didn’t occur to him, or did not seem to him to be an issue. For Packer, the moral imperative of conservation comes first.

Once again, conservationists are blaming the wrong people. Far fewer lions are killed by tribal peoples defending their villages than are shot by trophy hunting tourists. But “The Hunt” made no mention of colonial or elite hunting in the past, or of trophy hunters in the present and offered barely any coverage of the corrupt poaching networks and habitat destruction that are really driving large mammals to extinction around the world.

This approach is a con that is harming conservation. It would be more ethical and humanitarian (not to mention easier and cheaper) for conservationists to work in partnership with local people, rather than pushing them aside.

My organization, Survival International, has been campaigning on this issue for some time. We often encounter confusion over why we are petitioning big conservation organizations, or even hostility to our claim that certain conservation policies have led to serious human rights abuses. Of course, we acknowledge that many species are critically threatened and steps need to be taken to address this.

But to do this by evicting peaceful people from their land and forcing them into the mainstream of urban-industrial society against their will is wrong. The big conservation organizations are guilty of supporting this. They rarely speak out against evictions. Human rights are not incompatible with effective environmental policy and conservationists must be held to account when there is evidence of abuses.

Nobody wants to see species going extinct due to human negligence or greed. But it is not tribal people who endangered the lion, the elephant, the tiger or any other of the animals featured in “The Hunt,” and it is not tribes who should have penitential conservation measures forced upon them.