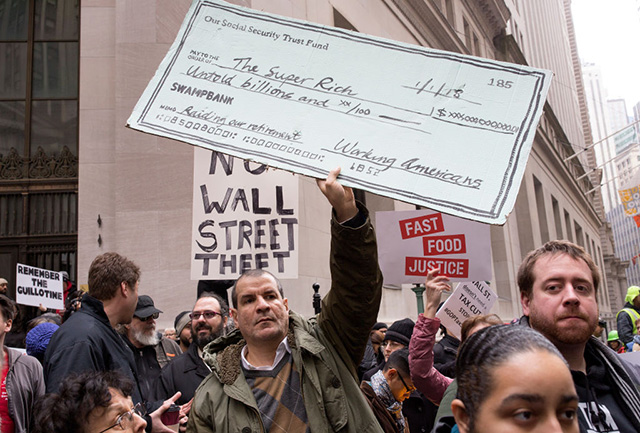

In response to the passage of the GOP tax bill, many voices are now offering variations on the theme of “speak truth to power.” It’s true enough that tax overhaul, coming after 30 years of widening inequality, widens it further. It is likewise yet another exercise in trickle-down economics, the policy promise that direct economic help to corporations and the rich will eventually lift up the rest of us. The GOP and Trump conveniently disregard the countless economists who have shown that trickle-down is a false promise.

However, the limitation of “speaking truth to power” is and always was that it risks leaving us with the truth and them with the power. In today’s world, the GOP, Trump and the corporate leaders who sustain them have the power to treat truths as so much “fake news” or simply to ignore them as they push their agendas. For the truth to become socially effective, it needs an alliance with an oppositional power able and willing to contest the ruling power.

In the US, until the 1970s, when truth meant advocating for a form of capitalism with a human face — regulated markets, safety nets, progressive taxation, generous public services — it could be allied chiefly to the Democratic Party and contest against the GOP. Likewise, for those who defined truth as advocating for a laissez-faire form of capitalism — deregulation, privatization, a reduced public sector — they could and did ally chiefly with the GOP and contest against the Democrats. But those connections between truth and power have changed since the 1970s, when moderate laissez-faire economics (neoliberalism) captured the Democratic Party and an extreme laissez-faire ideology captured the Republican Party.

The primary loyalty of major donors is to the capitalist system that undergirds their social position.

Another way to describe what has happened since the 1970s is that the central economic contest stopped being between Keynesian and neoclassical economics — between more and less government intervention in the economy. The central political contest used to be between left and right supporters of alternative forms of capitalism.

Now, in a capitalism where Democrats like Clinton boast of having ended the welfare safety net “as we know it,” more or less minimal government support of the mass of the people has become accepted policy for both major parties. As Nancy Pelosi said in response to a student’s question about socialism during the 2016 presidential election, “we are all capitalists.” She was referring to both major political parties. Her words marked an unconscious recognition that capitalism itself — not its alternative forms — is now the power being contested. Nor could she imagine that the student’s question was itself the speaking of a new truth to the power of capitalism as such.

The Democrats as a party currently do little more than speak their truth to GOP power. They do not act as or collaborate with or try to build a real social opposition. As far as the party goes, there are no demonstrations, no mass mobilizations: The Democrats vote and lose and make weak speeches to ever-smaller audiences. Democrats seem to fear losing major donations and donors were they to mount real opposition. The primary loyalty of major donors is to the capitalist system that undergirds their social position. This or that form of capitalism is of much less importance. The GOP gets this, too. Both parties now pander to the same donors; they have become, more than before, two wings of a party unified in its devotion to capitalism.

The GOP and Trump grasped this in putting forth the tax bill. Its tax cuts promise even more to capitalist corporations and those they enrich (major shareholders and top executives) than the traditional Republican and Democratic leaders would have dared to advocate even a couple of years ago. In response, the Democratic Party limited its opposition to speaking some truth to power. It avoided mass mobilizations whose demands might begin to include anti-capitalism, even in its most modest Sanders form.

What neither party grasps is that, as their theoretical and practical differences over forms of capitalism shrank, the system itself became again the issue. An entire generation grew up amid the oscillation between GOP and Democratic administrations and Congresses since the 1970s. That generation watched and learned as both major parties supported and sustained capitalism, speaking and acting as though no other system existed or was worth considering. That same generation has acutely experienced capitalism’s flaws and failures: poor job opportunities, school debt, grotesque inequality, and so on. It has done so without the Cold War context of a lopsided celebration of capitalism and over-the-top demonization of its critics. Especially since the crash of 2008, that generation has shown a greater consciousness of the potential power of alternative systems, and has come to question, challenge and shift its loyalties away from capitalism.

The politically self-absorbed disregard of the major parties, combined with the ascendance of remarkably repulsive leaders like Trump, Ryan, McConnell, Pelosi and Schumer (not to mention many, many others at lower levels) only further alienates the young. The truths of younger generations, now spoken ever louder to power, are also wakening to the need for an alliance with a socially effective power to contest against both the GOP and the Dems.

We live in a time rich with ironies. After 1989 and the implosion of the USSR, a kind of capitalist triumphalism hailed the “end” of the capitalism versus socialism theme that so dominated the 20th century. Capitalism, we were told, had “won.” A generation later, capitalism finds itself in deepening difficulties: economic, political and ideological. Socialisms of various kinds have re-emerged as alternatives to an increasingly contested capitalism.

In this new era, what does “socialism” mean? There remain, of course, the remnants of what socialism meant in the 20th century. Those faithful to that socialism still view it as a state-focused economic system. In it, state ownership of means of production (rather than capitalism’s private ownership) partners with state-planned distribution of resources and products (rather than capitalism’s markets). Socialists of this variety continue to see their version as the only viable alternative to capitalism and its eventual successor.

However, other kinds of socialism are increasingly challenging those remnants among the critics of capitalism. Many of these reflect socialist self-criticisms constructed around key history-based questions: “Why did the USSR implode?” “Why have the People’s Republic of China and other ‘socialist’ economies opened increasingly to private capitalist enterprises?” “How did the statism of socialist economies contribute to undemocratic political and cultural systems?”

Meanwhile, new and different socialisms have emerged. There are libertarian or anarchically inflected socialisms that stress local, decentralized, non- or anti-statist variations with or without market institutions linking enterprises and individuals to one another. Democratic socialisms — some old and some new — have also emerged, stressing the necessary co-existence of democratic political institutions with socialist economies interpreted in either libertarian or else strictly-limited statist variants.

Then there is a socialism whose approach is to refocus priorities on the micro-level — the enterprise — rather than the macro-level — the state. In this version, the emphasis is on the radical reorganization of the enterprise, away from the hierarchical capitalist to the democratic cooperative. In the latter, workers become their own collective employer as the division between employee and employer dissolves. Workers’ democratic decisions then govern what gets produced with which technology, where and when; their democratic decisions also govern the use made of the profits they collectively produced. Such a socialism leaves open the question of whether such democratized enterprises will co-exist with markets or state planning. The general presumption is that the democratized enterprises will erect and adjust their distributional system to reinforce the cooperative structure of their enterprises, much as capitalist enterprises structured markets to reinforce theirs.

In the ongoing process of transition from capitalism to the next system, capitalism’s critics are extending and deepening the truths they speak. They are increasingly directing those truths to the power of capitalism as expressed in the policies and politics of both Republicans and Democrats. They are looking and working for an alliance with real, organized oppositional political power, even as they are building it themselves. They want a powerful partner for their truth.

This is one place we can find hope, even in the wake of the devastating tax bill’s passage. Here, there is real hope for real change.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.