Part of the Series

The Public Intellectual

Too many universities are now beholden to big business, big sports and big military contracts. And it is within this new set of contexts that we must read the Penn State scandal. Much media attention has been drawn to the fact that Penn State pulls in tens of millions of dollars in football revenue, but nothing has been said of the fact that it also receives millions from Defense Department contracts and grants, ranking sixth among universities and colleges receiving funds for military research.(1) Or that as a result of considerable influence by corporate interests, the academic mission of the university is now less determined by internal criteria established by faculty researchers with the knowledge expertise and a commitment to the public good than by external market forces concerned with achieving fiscal stability and, if possible, increasing profit margins. The excesses to which such practices have given rise have proven obscene to the point of the pornographic. One has only to look closely at the unfolding tragedy at Penn State University to understand the potentially catastrophic consequences of this decades-long transformation in higher education for universities more generally.

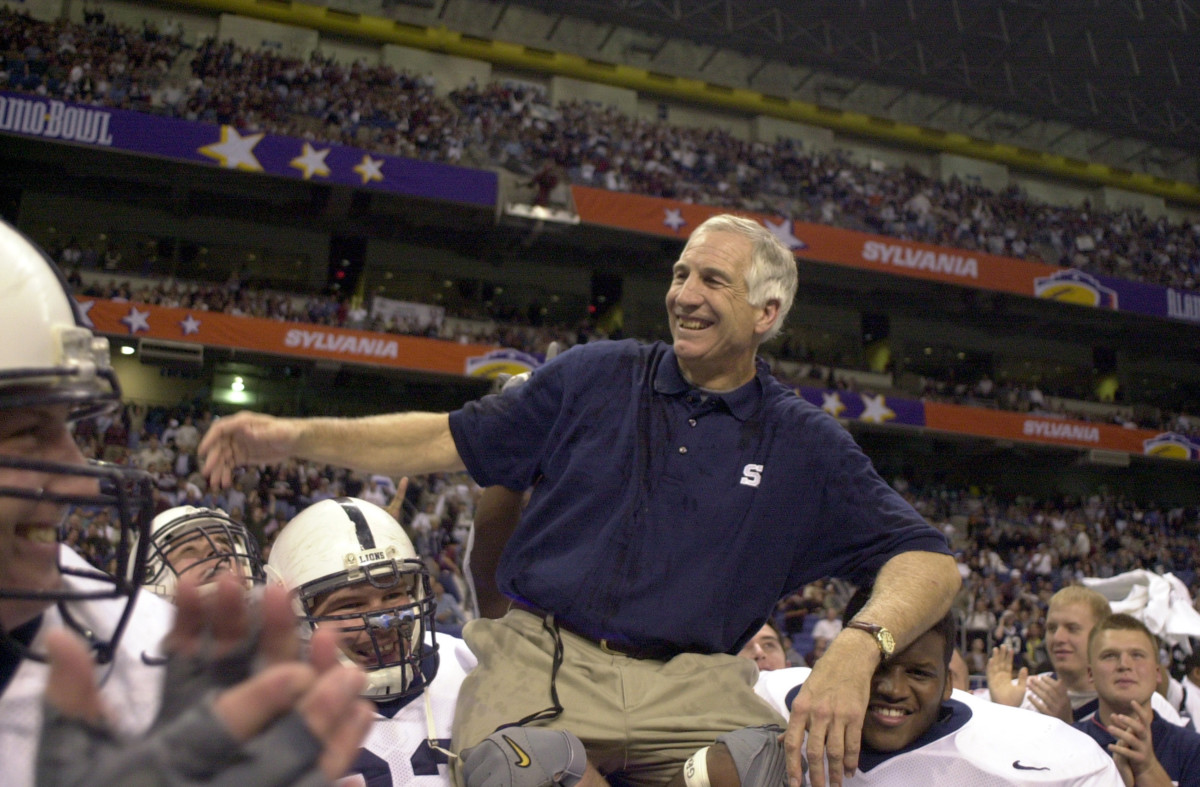

The Penn State crisis may well prove one of the most serious scandals in the history of college athletics and university administration, while it also reinforces the claim, made by Paul Krugman, “that democratic values are under siege in America.”(2) Jerry Sandusky, who coached the Nittany Lions for more than 30 years, allegedly used his position of authority at the university as well as at his Second Mile Foundation, a foster home, to lure vulnerable minors into situations in which he preyed on them sexually, having gained unfettered access to male youths through a range of voluntary roles.(3) Sandusky has been charged with sexually abusing at least a dozen boys, all of whom were twelve years old or younger when they were attacked. On at least three occasions, extending from 1998 to 2002, Sandusky was caught abusing young boys on the Penn State campus. These incidents have been the consistent focus of media attention. In 1998, a distraught mother of a boy who had showered with Sandusky reported the incident to the campus police. A janitor also observed Sandusky performing oral sex on a young boy in a Penn State gym in 2000. Finally, according to the grand jury report in the Sandusky case, Mike McQueary, a 28-year-old graduate assistant for the Penn State football team, alleged that in 2002 he saw Sandusky raping a young boy in the shower in the Lasch Football Building on the University Park campus. It has, therefore, taken nine years for the police to investigate and finally arrest Sandusky, who has now been charged with over 50 counts of sexual abuse.

As tantalizingly sensational as the media have found these events, the scandal is about much more than a person of influence using his power to sexually assault innocent young boys. This tragic narrative is as much about the shocking lengths to which rich and powerful people and institutions will go in order to cover up their complicity in the most horrific crimes and to refuse responsibility for egregious violations that threaten their power, influence and brand names.(4) The desecration of public trust is all the more vile when the persons and institution in question have been assigned the intellectual and moral stewardship of generations of youth.

The most recent cover-up appears to have begun in 1998 when Centre County District Attorney, Ray Cricar, did not file charges against Sandusky, in spite of obtaining credible evidence that Sandusky had molested two young boys in a shower at Penn State. Then, in 2000, the janitor who witnessed similar abuse and his immediate superior, whom he told about it, both failed to report the incident to the police for fear of losing their jobs, only to reveal the story years later. But the cover-up that has attracted the most attention took place in 2003 after Mike McQueary reported to celebrated coach Joe Paterno that he saw Sandusky having anal intercourse with a ten-year-old boy in one of the football facility’s showers. Paterno reported the incident to his athletic director, Tim Curley, who then notified Gary Schultz, a senior vice president for finance and business. Both informed President Spanier about the incident. In light of the seriousness of a highly credible and detailed report alleging that a child had been raped, the Penn State administration simply responded by barring Sandusky from bringing young boys onto the university campus. At the end of the day, neither Paterno nor any of the highly positioned university administrators reported the alleged assault of a minor to the police and other proper authorities. Within a week after the story broke in the national media eight years later, Paterno, Schultz, Curley and Spanier had all been fired. Sandusky “now faces more than 50 charges stemming from accusations that he molested boys for years on Penn State property, in his home and elsewhere.”(5) The charges include involuntary sexual intercourse, indecent assault, unlawful contact with a minor, corruption of minors and endangering the welfare of a minor.

In the most shameful of ironies, the national response to the story has similarly engaged in a covering up of the violent victimization of children that lay at its core. The young boys who have been sexually abused have been relegated to a footnote in a larger and more glamorous story about the rise and sudden fall of the legendary Paterno, a larger-than-life athletic icon. Their erasure is also evident in the equally sensational narrative about how the university attempted to hide the horrific details of Sandusky’s history of sexual abuse by perpetuating a culture of silence in order to protect the privilege and power of the football and academic elite at Penn State. If any attention was paid at all to distraught and disillusioned youth, it was to focus on the Penn State students who rallied around “Joe-Pa,” not on the youth who bore the weight into their adulthood of being victims of the egregious crimes of rape, molestation and abuse. As many critics have pointed out, both dominant media narratives fail to register just how deeply this tragedy descends in terms of what it reveals about our nation’s priorities about youth and our increasing unwillingness to shoulder the responsibility – as much moral and intellectual as financial – for their care and development as human beings.

Michael Bérubé rightly asserts that the scandal at Penn State and the ensuing “student riots on behalf of a disgraced football coach” should not be used to condemn the vast majority of teachers, researchers and students at Penn State, “none of whom had anything to do with this mess.”(6) Equally pertinent is his observation that Penn State has a long history of rejecting any viable notion of shared governance and that “decisions, even about academic programs, are made by the central administration and faculty members are ‘consulted’ afterward.”(7) The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) extended Bérubé’s argument, insisting that the lack of faculty governance has to be understood as a consequence of a university system that favors the needs of a sports empire over the educational needs of students, the working conditions of faculty and health and safety of vulnerable children.(8)

The call for forms of shared governance in which faculty through their elected representatives are treated with respect and exercise power alongside administrators signals an important issue – namely, how many university administrations operate in nontransparent and unaccountable ways that prioritize financial matters over the well-being of students and faculty? At the same time, it is not uncommon for entrepreneurial faculty members to transgress established strategic priorities and circumvent layers of university oversight and adjudication altogether by bringing in earmarked funding for a pet project (through which s/he stands to gain), confident no administrator can refuse cash up front, whatever the Faustian bargain attached to it.

Big money derived from external sources has changed the culture of universities across the United States in still other ways. For example, in 2010, Penn State made $70,208,584 in total football revenue and $50,427,645 in profits; moreover, it was ranked third among American universities in bringing in football revenue. As part of the huge sports enterprise that is NCAA Division I Football, Penn State and other high profile “Big Ten” universities not only make big money, but also engage in a number of interlocking campus relationships with private-sector corporations. Lucrative deals that generate massive revenue are made through media contracts involving television broadcasts, video games and Internet programming. Substantial profits flow in from merchandizing football goods, signing advertising contracts and selling an endless number of commodities from toys to alcoholic beverages and fast food at the stadium, tailgating parties and sports bars. Yet, the flow of capital is not unidirectional.

Universities also pay out impressive amounts of money to support such enterprises and to attract star athletes; they hire support staffing from janitorial positions to top physicians in sports medicine to celebrity coaches; they pay to maintain equipment, grounds, stadia and myriad other associated services. Consider Beaver Stadium – the outdoor college football monument to misplaced academic priorities – which has a capacity of 106,572 seats that require cleaning and maintenance. The stadium holds as many people as the entire population of State College, including Penn State students – all of whom require armies of staff to accommodate their needs. In this instance, the circulation of money and power on university campuses mimics its circulation in the corporate world, saturating public spaces and the forms of sociality they encourage with the imperatives of the market. Money from big sports programs also has an enormous influence on shaping agendas within the university that play to their advantage, from the neoliberalized, corporatized commitments of an increasingly ideologically incestuous central administration to the allocation of university funds to support the athletic complex and the transfer of scholarship money to athletes rather than academically qualified, but financially disadvantaged students. As Slate writer J. Bryan Lowder puts it, big sports “wield too much influence over college life. In an institution that is meant to instill the liberal values of critical thinking and an egalitarian sense of equality in its students, having special dining rooms or living quarters for athletes … is a bad idea.”(9)

What should be deeply unsettling and yet remains unspoken in mainstream media analyses is that the youth have also learned these lessons at the university, where they have been immersed in a culture that favors entertainment over education – the more physical and destructive, the better; competition over collaboration; a worshipful stance toward iconic sports heroes over thoughtful engagement with academic leaders, who should inspire by virtue of their intellectual prowess and moral courage; and herd-like adhesion to coach and team over and against one’s own capacity for informed judgment and critical analysis. The consolidation of masculine privilege in such instances enshrines patriarchal values and exhibits an astonishing indifference to repeated cases of sexual assaults on college campuses.

Sexual assault is a problem on college campuses across the United States, as revealed in national statistics demonstrating that “one in five women [was] sexually assaulted while in college and approximately 81 percent of students experienced some form of sexual harassment during their school years.”(10) However, in the years we taught at Penn State, it reached alarming proportions. According to the Center for Women Students on the university’s main campus, “At Penn State approximately 100 students sought assistance for sexual assault during the 1996-97 academic year.”(11) For those familiar with the behavior often exhibited by victims of sexual violence, the fact that 100 students came forward in a single year is simply shocking, given the overwhelming reticence most victims feel about reporting attacks. In addition to feeling fear and shame, the reluctance to report an assault is reinforced when the victim believes that it will seldom result in arrest or conviction. Put simply, this means that the extent of cases and many of the consequences of sexual assault, physical abuse, hazing and violence on college campuses are probably much greater than what is actually known.

Claire Potter, writing in the Chronicle of Higher Education, argues that Penn State and universities in general have a vested interest in safeguarding their reputations by covering up acts of sexual violence. For Potter, “Universities substitute private hearings, counseling and mediation for legal proceedings: while women often choose this route, rather than filing felony charges against their assailants, it doesn’t always serve their interest to do so. But it always serves the interests of the institution not to have such cases go to court.”(12) Given how events have unfolded at the university, Potter’s withering charge that Penn State has a greater interest in protecting its brand name than in protecting students – who are reduced to revenue-producing entities rather than seen as young people to whom it has the responsibility intellectually and ethically to shape and inspire – gains considerable force. For Potter, social power at universities dominated by a big sports culture often expresses itself not just in the glory of the game, the reputation of the coaches, or the herd-like devotion to a team, but also in forms of sexual power aimed at abusing female students. Potter wants to move these incidents away from the sports pages and popular media into classrooms where they can be understood within a larger set of economic, social and political contexts and appropriately challenged.

The hardened culture of masculine privilege, big money and sport at Penn State is reinforced as much through a corporate culture that makes a killing off the entire enterprise as it is through a retrograde culture of illiteracy – defined less in terms of an absence of knowledge about alternatives to normative gender behavior and more in terms of a willfully embraced ignorance – that is deeply woven into the fabric of campus life. Even and especially in higher education, one cannot escape the visual and visceral triumph of consumer culture, given how campuses have come to look like shopping malls, treat students as customers, confuse education with training and hawk entertainment and commodification rather than higher learning as the organizing principles of student life. Across universities, the ascendancy of corporate values has resulted in a general decline in student investment in public service, a weakening of social bonds in favor of a survival-of-the-fittest atmosphere and a pervasive undercutting of the traditional commitments of a liberal arts education: critical and autonomous thinking, a concern for social justice and a robust sense of community and global citizenship.

As academic labor is linked increasingly to securing financial grants or downsized altogether, students often have little option than to take courses that have a narrow instrumental purpose and those who hold powerful administrative positions increasingly spend much of their time raising money from private donors. All the while, students accrue more debt than ever before; student debt, in fact, has now surpassed the accumulated credit card debt in a nation of notoriously robust consumers. The notion that the purpose of higher education might be tied to the cultivation of an informed, critical citizenry capable of actively participating and governing in a democratic society has become cheap sloganeering on college advertising copy, losing all credibility in the age of big money, big sports and corporate influence. Educating students to resist injustice, refuse anti-democratic pressures, or learn how to make authority and power accountable remains at best a receding horizon – in spite of the fact that such values are precisely why universities are pilloried by moneyed Republicans as hotbeds of Marxist radicals.

The displacement of academic mission by a host of external corporate and military forces surely helps to explain the spontaneous outbreak of rioting by a segment of Penn State students once the university announced that Joe Paterno has been fired as the coach of the storied football team. Rather than holding a vigil for the minors who had been repeatedly sexually abused, students ran through State College wrecking cars, flipping a news truck, throwing toilet paper into trees and destroying public property. J. Bryan Lowder understands this type of behavior as part of a formative culture of social indifference and illiteracy reinforced by the kind of frat house insularity that is produced on college campuses where sports programs and iconic coaches wield too much influence. He writes:

Building monuments to a man whose job is, at the end of the day, to teach guys how to move a ball from one place to another, is … inappropriate. And, worst of all, allowing the idea that anyone is infallible – be it coach, professor or cleric – to fester and infect a student body to the point that they’d sooner disrupt public order than face the truth is downright toxic to the goals of the university…. Blind, herd-like dedication to a coach or team or school is pernicious. Not only does it encourage the kind of wild, unthinking behavior displayed in the riot, but it also fertilizes the lurid collusion and willful ignorance that facilitated these sex crimes in the first place. But what to do? As David Haugh asked in The Chicago Tribune: “When will [the students] realize, after the buzz wears off and sobering reality sinks in, that they were defending the right to cover up pedophilia?”(13)

Phil Rockstroh extends Lowder’s analysis, rightfully connecting the political illiteracy reflected in the student rampaging at Penn State to a wider set of forces characterizing the broader society to the obvious detriment of students. He writes:

Penn. State students rioted because life in the corporate state is so devoid of meaning … that identification with a sports team gives an empty existence said meaning … These are young people, coming of age in a time of debt-slavery and diminished job prospects, who were born and raised in and know of no existence other than life as lived in U.S. nothingvilles i.e., a public realm devoid of just that – a public realm – an atomizing center-bereft culture of strip malls, office parks, fast food eateries and the electronic ghosts wafting the air of social media. Contrived sport spectacles provisionally give an empty life meaning … Take that away and a mindless rampage might ensue … Anything but face the emptiness and acknowledge one’s complicity therein and then direct one’s fury at the creators of the stultified conditions of this culture.(14)

A number of critics have used the Penn State scandal to call attention to the crisis of moral leadership that characterizes the neoliberal managerial models that now exert a powerful influence over how university administrations function. As the investment in the public good collapses, leadership cedes to reductive forms of management, concerned less with big ideas than with appealing to the pragmatic demands of the market, such as raising capital, streamlining resources and separating learning from any viable understanding of social change. Anything that impedes profit margins and the imperatives of instrumental rationality with its cult of measurements and efficiencies are seen as useless. Within the logic of the new corporate-driven managerialism, there is little concern for matters of justice, fairness, equity and the general improvement of the human condition insofar as these relate to expanding and deepening the imperatives and ideals of a substantive democracy.(15) Discourses about austerity, budget shortfalls, managing deficits, restructuring and accountability so popular among college administrators serve largely as a cover “for a recognisably ideological assault on all forms of public provision.”(16)

If university administrators cannot defend the university as a public good, but instead, as in the case of Penn State, align themselves with big money, big sports and the instrumental values of finance capital, they will not be able to mobilize the support of the broader public and will have no way to defend themselves against the neoliberal and conservative attempts by state governments to continually defund higher education. In recent years, universities have not thought twice about placing the burden of financial shortfalls on the backs of students – even as that burden grows apace, wrought by austerity measures, or by internal demands for new resources and space to keep up with record growth, or by new competition with international and online educational institutions. All this amounts to a poisonous student tax, one that has the consequence of creating an enormous debt for many students. Penn State has one of the highest tuition rates of any public college – amounting to $14,416 per year. But it is hardly alone in what has become a pitched competition to raise fees. Some public colleges such as Florida State College have increased tuition by 49 percent in two years! The lesson here is that abuse of young people comes in many forms, extending from egregious acts of child rape and sexual violence against women to the creation of a generation of students burdened by massive debt and a bleak, if not quite hopeless, jobless future.

The Penn State scandal is symptomatic of a much larger set of challenges – and the abuses they almost invariably invite – which are deeply interconnected and mutually informing. On the one hand, Penn State symbolizes the corruption of higher education by big sports, governmental agencies and corporate power with vested interests and deep pockets. On the other hand, the tragedy can surely be seen as a part of what we have been calling the war on youth. The media emphasis on the fall of Paterno, the firing of high-ranking university administrators and the alleged failure of a chain of command, while not incidental to the ongoing abuse of over a dozen boys, serves ironically to deflect attention from the egregious sexual assault of young boys, who have carried this grievous burden into their adulthood. Students, faculty and administrators also pay a terrible price when a university loses its moral compass and refashions itself in the values, principles and managerial dictates of a corporate culture.

Neither the media accounts of the rise and fall of a celebrity coach nor what many insiders would like to characterize as a woeful series of administrative miscommunications tell us much about how Penn State is symptomatic of what has happened to a number of universities since at least the mid-1940s and at a quickened pace since the 1980s. Penn State, like many of its institutional peers, has become a corporate university caught in the grip of the military-industrial complex rather than existing as a semi-autonomous institution driven by an academic mission, public values and ethical considerations.(17) It is a paradigmatic example of mission drift, one marked by a fundamental shift of the university away from its role as a vital democratic public sphere toward an institutional willingness to subordinate educational values to market values. As Peter Seybold has suggested, the Penn State scandal is indicative of the ongoing corruption of teaching, research and pedagogy that has taken place in higher education.(18) Beyond the classroom and the lab, evidence of ongoing corporatization abounds: bookstores and food services are franchised; part-time labor replaces full-time faculty; classes are oversold; and online education replaces face-to-face teaching, less as a pedagogical innovation and more as a means to deal with the capacity issues now confronting those universities that pursued financial sustainability through aggressive growth.(19) It gets worse. The corporate university is descending more and more into what has been called “an output fundamentalism,” prioritizing market mechanisms that emphasize productivity and performance measures that make a mockery of quality scholarship and diminish effective teaching – scholarly commitments are increasingly subordinated to bringing in bigger grants to supplement operational budgets negatively impacted by the withdrawal of governmental funding.

In addition, the student experience has hardly been untouched by these shock waves, which have further undermined the genuinely intellectual, financial, social and democratic needs of undergraduate and graduate students alike. Young people are increasingly devalued as knowledgeable, competent and socially responsible, in spite of the fact that their generation will inevitably be the leaders of tomorrow. Put bluntly, many university administrators demonstrate a notable lack of imagination, conceiving of students primarily in market terms and showing few qualms about subjecting young people to forms of education as outmoded as the factory assembly lines they emulate. Campus extracurricular activities unfold in student commons designed in the image of shopping centers and high-end entertainment complexes. Clearly, students are not perceived as worthy of the kinds of financial, intellectual and cultural investments necessary to enhance their capacities to be critical and informed individual and social agents. Nor are they provided with the knowledge and skills necessary to understand and negotiate the complex political, economic and social worlds in which they live and the many challenges they face now and will face in the future. Instead of being institutions that foster democracy, public engagement and civic literacy, universities and colleges now seduce and entertain students as prospective clients, or, worse yet, act as recruitment offices for the armed forces.(20) In other words, students are being sold on a certain type of collegial experience that often has very little to do with the quality of education they might receive, while university leaders appear content to have faculty provide entertainment and distraction for students in between football games.

Against the notion that the neoliberal market should organize and mediate every human activity, including how young people are educated, we need to develop a new understanding of democratic politics and the institutions that make it possible; we also need to organize individually and collectively to create the formative cultures that teach students and others that “they are not fated to accept the given regime of educational degradation” and the eclipse of civic and intellectual culture in and outside of the academy.(21) What is crucial to recognize is that higher education may be the most viable public sphere left in which democratic principles and modes of knowledge and values can be taught, defended and exercised. Surely, public higher education remains one of the most important institutions in which a country’s commitment to young people can be made visible and concrete. The scandal at Penn State illuminates a profound crisis in American life, one that demands critical reflection – for those inside and outside the academy – on the urgent challenges facing higher education as part of the larger interconnecting crisis of youth and democracy. It demands that we connect the dots between the degradation of higher education and those larger economic, political, cultural and social forces that benefit from such an unjust and unethical state of affairs – and which, in the end, young people will pay for with their sense of possibility and their hope for the future. Learning from the Penn State scandal requires that faculty, parents, artists, cultural workers, and others listen to students who are mobilizing all across the country and around the world as part of a broader effort to reclaim a democratic language and political vision. These insightful and motivated youth are rejecting the narrow prescriptions and heavy burdens that would be foist upon them, and choosing instead to invent a new understanding of what it means to make substantive democracy possible.

A much larger and more detailed version of this paper will appear in the next issue of JAC under the title: “Scandalous Politics: Penn State and the Return of the Repressed in Higher Education.”

Footnotes:

1. For an excellent analysis of the weaponizing of higher education, see David H. Price, “Weaponizing Anthropology” (Oakland: AK Press, 2011). See also, Henry A. Giroux, “The University in Chains: Confronting the Military-Industrial-Academic Complex,” (Boulder: Paradigm, 2007).

2. Paul Krugman, “Depression and Democracy,” New York Times (December 12, 2011), p.23

3. Center County Grand Jury Indictment against Gerald A. Sandusky. (December20, 2011). Online here, p. 3.

5. Los Angeles Times. “Jerry Sandusky Arrested on New Charges of Child Sex Abuse: The Former Penn State Assistant Football Coach Faces More than 50 Child Sex Abuse Charges.” LATimes.com (December 7, 2011). Online here. See also, StateCollege.com. “Penn State Charges: News on the Cases against Sandusky, Curley and Schultz,” (December 20,. 2011). Online here.

6. Michael Bérubé, “At Penn State, a Bitter Reckoning,” New York Times (November 17, 2011), p. A33.

8. Cary Nelson and Donna Potts. “The Dangers of a Sports Empire.” AAUP Newsroom. (November 29, 2011). Online here.

9. Bryan J. Lowder, “The Danger of Joe Paterno’s ‘Father-Figure’ Mystique.” Slate (November. 2011). Online here.

10. Katherine Greenier, “From Fear to Safety: Confronting Sexual Assault and Harassment on Campuses.” RH Reality Check (November 21. 2011). Online here.

11. Penn State Division of Student Affairs. “Know the Facts – Rape and Sexual Assault.” Penn State Center for Women Students. (December 20, 2011). Online here.

12. Claire Potter, “The Penn State Scandal: Connect the Dots Between Child Abuse and the Sexual Assault of Women on Campus.” Chronicle of Higher Education (Nov. 10, 2011). Online here.

13. Bryan J. Lowder, “The Danger of Joe Paterno’s ‘Father-Figure’ Mystique.” Slate (November. 2011). Online here.

14. Phil Rockstroh, “The Police state Makes Its Move: Retaining One’s Humanity in the Face of Tyranny,” Common Dreams.org (November 15, 2011). Online here.

15. Henry A. Giroux, “Against the Terror of Neoliberalism,” (Boulder: Paradigm, 2008).

16. Stefan Collini, “”Browne’s Gamble.” London Review of Books 32.21 (4 November 4, 2010). Online here.

17. Op. cit., Giroux, University in Chains.

18. Peter Seybold, “The Struggle against Corporate Takeover of the University.” Socialism and Democracy 22.1 (March 2008): 1-11.

19. Seybold quoted in Steven Higgs, “The Corporatization of the American University,” CounterPunch (November 21, 2011). Online here.

20. See Op. cit., Price and also Nick Turse, “The Complex: How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives,” (New York: Metropolitan, 2008).

21. Stanley Aronowitz, “Against Schooling: Toward an Education That Matters,” (Boulder: Paradigm, 2008), p. 118.

We have 9 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.