Part of the Series

Solutions

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta will lay out a plan today to cut the Pentagon's budget as required by the White House and the Congress. He isn't happy about it and has complained bitterly in the media about hollowing out the military, and he has had help from the top generals in the Department of Defense (DoD) to give him backup.

However, studies that I started years ago show that there are way too many generals for troops, planes and ships and these generals also make sure that their turf and positions are protected. They are costing us far more than their high salaries, retirements and perks; they are using their positions to protect the status quo in the military.

Ironically, they are fighting budget cuts that would take them, in constant dollars, back to 2007 levels of spending. To put that in historic perspective, the DoD budget has nearly doubled since 9/11.

So, how many military brass do we have compared to past years? We have the most ever since World War II. In 1982, when I was running the Project on Military Procurement, one of my sources suggested to me that I do research on how many top officers we had for our troops, planes and ships. My report showed a steady increase since World War II, especially since the number of planes and ships were decreasing due to cost, while the number of generals were increasing. Over the years, my former organization, now known as the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) (for full disclosure, I am on POGO's board of directors and serve as treasurer), has redone the report several times, and the brass continues to grow as we get fewer and fewer weapons. The biggest growth was with three- and four-star generals, which POGO has dubbed “star creep.” POGO's Ben Freeman recently testified to the Congress in September on how bad the problem had gotten. From his testimony:

The three- and four-star ranks have increased twice as fast as one- and two-star general and flag officers, three times as fast as the increase in all officers and almost ten times as fast as the increase in enlisted personnel. If you imagine it visually, the shape of U.S. military personnel has shifted from looking like a pyramid to beginning to look more like a skyscraper (i.e. higher ranks having fewer lower ranking personnel under them rather than more)….

On average, there are now approximately 185 fewer enlisted personnel per general in the Air Force and 400 fewer enlisted per admiral in the Navy than there were just ten years ago. Similarly, there are more than 40 fewer officers per general or flag officer in both the Air Force and Navy today than there were in 2001.

But this only begins to scratch the surface of this irregularity. During this same time period the Navy and Air Force cut both enlisted personnel (65,205) and officers (5,369), while the Army and Marines added both enlisted personnel (94,401) and officers (23,108). Thus, the Navy and Air Force added more three- and four-stars even as they cut their forces. Meanwhile, the Army and Marines who presided over a growing force increased their three- and four-star billets at a much slower rate.

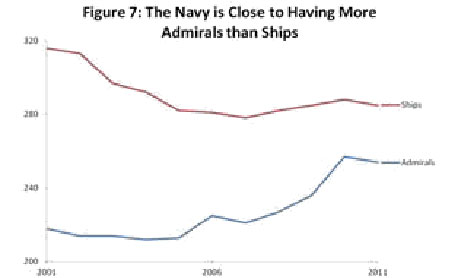

There has also been a significant reduction in the number of weapons systems utilized by both the Navy and the Air Force. The Navy now has 32 fewer active ships and the Air Force operates 576 fewer aircraft than they did in 2001. [See footnote 24 here.] If the Navy continues to add admirals as it has throughout the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and reduce the total number of ships in its fleet it will, in the very near future, have more admirals than ships for them to command, as shown in Figure 7. By way of comparison, in 1986 during the Reagan Cold War buildup, there were more than two ships per admiral; when the Vietnam War ended in 1969 there were nearly three ships per admiral; and, when World War II ended there were approximately 130 ships per admiral. [See footnote 25 here.]

Although not on pace with the Air Force and Navy, star creep within the Army and Marines is also apparent. The Army has decreased its number of one-star generals, while increasing its higher ranking generals. Specifically, the Army cut 13 brigadier generals between September 2001 and April 2011, but added 11 major generals, 11 lieutenant generals and two four-star generals. Thus, even within the general and flag officer ranks, it is the higher ranks that are being added while only brigadier generals are being cut. The Marines' story is very similar: five brigadier generals were cut during this time period, seven major generals were added and four lieutenant generals were added. Since September 2001, three- and four-star officers in the Army and Marines have increased by 25 and 24 percent, respectively.

So, we are continuing to add three- and four-star generals while our planes and ships shrink. The Pentagon doesn't want to lose these weapons, but it has allowed the prices of these weapons to go out of control. This irony will only get worse if the Pentagon continues to overprice their weapons while increasing their top brass. My column on what to do about the disastrous pricing of weapons shows that this trend will continue unless the Pentagon changes the basis of pricing weapons. Previews of Secretary Panetta's plans suggest that he is planning to retire or eliminate more weapon systems.

Former Secretary Robert Gates had his representatives at the hearing promise that there would be a planned cut in the number of military brass. However, when Secretary Panetta took over, these plans were laid aside as the number of brass actually increased and the reforms were sabotaged. POGO's blog piece by Ben Freeman shows how plans to cut the generals were sabotaged, even as they were telling the Congress that they are fixing the problem:

My fellow witnesses at the hearing – several generals and admirals as well as former Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness Clifford Stanley – assured the concerned Committee that they had everything under control. They cited Gates' Efficiency Initiatives, which purportedly eliminate 102 general and flag officer positions, as evidence of the DoD's commitment to combating Star Creep. Stanley confirmed to Chairman Jim Webb (D-VA) that Gates' successor – Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta – supported these efforts and, “has accepted the policies and the things put in place by his predecessor.” (Stanley tendered his notice of resignation in late October.)

What Senator Webb and I did not know at the time – and perhaps Stanley did – was that Gates' initiative to cut general and flag officers had already come to a screeching halt. Data that were released recently on the DoD personnel office's website tell the tale …

When POGO began its analysis of Star Creep, the most recent data available to the public were from April 2011. Thus, when I presented Chairman Webb our recommendation that Secretary Panetta work to fully enact Gates' Efficiency Initiatives to combat Star Creep and heard the other witnesses declare their support for the initiatives, I had no way of knowing that the DoD had already completely reversed course on Gates' efforts.

Seventeen general and flag officers were scheduled to be eliminated between May and September through Gates' Efficiency Initiatives. But the DoD didn't reduce its top brass at all. Instead, six generals were added from May to September, increasing the number of general and flag officers from 964 to 970. Moreover, from July 1, 2011 – Panetta's first day as Secretary of Defense – to September 30, the Pentagon added three four-star officers. Coincidentally, this is precisely the number of four-star officers Gates cut during his final year as SecDef, from June 2010 to the end of June 2011. Thus, in just three months, Panetta undid a year's worth of Gates' attempts to cut the Pentagon's very top brass. It's doubtful that Gates would consider Panetta's current rate of adding a new four-star officer every month conducive to efficiency.

One of these new four-star officers is Admiral Mark Ferguson, who became vice chief of naval operations and consequently a four-star admiral less than a month before he testified at Senator Webb's hearing. Ironically, this beneficiary of Star Creep wrote in his prepared statement that the “Navy supports these efficiency actions and anticipates additional review to reduce or merge flag officer positions.” At the hearing he expanded upon this, stating that “We [the Navy] remain absolutely committed to create a more agile, flexible and effective flag officer staff structure.” Apparently, this support and commitment to flag officer efficiencies includes adding admirals.

In his testimony, Freeman also talked about how much these three- and four-star generals cost in salary, housing, retirement etc. While that is important, I am much more concerned about how much this bloated officer corps, especially the top brass, is costing us in their influence and the need for each one of them to have a large staff below them to do less and less work. Their large presence makes it much harder to reform the Pentagon.

I have attended many DoD hearings on Capitol Hill over the years and it has always been darkly humorous to me how the top brass arrive to testify. If the hearing was about a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on problems of a specific weapon system, the GAO officials, usually about two to three of them, would arrive without fanfare. But when the four-star general would arrive to testify, there would be a great flurry of activity as he walked in the room with several three-star generals, three to four one- and two-star generals and a flurry of lower officers scurrying ahead to set up the presentation and charts. They used to take up the whole first and some of the second row behind the witness table with lots of charts and graphs shuffling around as the great man sat down. It was known on the Hill as the flotilla, and it was actually sad to see full-bird colonels masquerading as chart bunnies for the four star.

As silly as it seemed to many of us in the room, it had an effect on the members of Congress. While most of the members from both parties were always happy to horsewhip top officials, including Cabinet members from other government departments, they have, for the most part, seemed hesitant if not reluctant to submit a three- or four-star general to the same treatment. The generals know how to speak Pentagonese (“We are working the problem on a time multiplex basis”), which makes it sound like they have everything under control while the flotilla behind them shuffle ersatz, complex information up to the general to further confuse and intimidate the members of Congress. Even when a member of Congress pushes back, they are probably wondering how this might look on C-SPAN back in their districts and usually don't bore down to the real information. Nobody wants to be seen beating up on a distinguished top officer in uniform, even if, in reality, he is just another obfuscating bureaucrat under those stars on his shoulders. This allows the DoD to get away with more fraud than other agencies.

After these high-ranking generals retire with generous pensions, many of them still seek out lucrative jobs with defense contractors, either as employees or as consultants. This is furthering the corruption of the weapons procurement budget as they work to subtly influence the military brass who used to be at a rank lower than them. Generals don't really retire and separate from the service; they are considered in retired status and can be called back. This is disastrous for the troops below these generals and breeds a cynicism to any of the honest officers below them and encourages others to follow in their footsteps.

In a past column, I suggest some rather strong solutions for retired military generals. To help solve the problem of this undue influence and resistance to desperately needed military reform, I would suggest the president should send a strong message to Secretary Panetta to cut the generals that Secretary Gates suggested and then prepare for more and more cuts, especially at the three- and four-star level. One of the ways to do that is to look at the jobs these three and four stars are doing and buck those jobs down to lower officers, even down to a colonel level so that these huge flotillas can be eliminated without hurting any mission. Many true warriors dread serving a post in the Pentagon because they know that, despite their officer rank, they could be in charge of holding the general's coat. We need to get our military back to doing military things and decrease these star ranks and all they currently represent in the system.

Secretary Gates saw this problem and commented on it in his August 2010 briefing on reforming the Pentagon:

… we have also seen an acceleration of what Senator John Glenn more than 20 years ago called “brass creep,” a situation where personnel of higher and higher rank are assigned to do things that could reasonably be handled by personnel of lower rank.

In some cases, this creep is fueled by the desire to increase bureaucratic clout or prestige of a particular service, function or region, rather than reflecting the scope and duties of the job itself. And in a post-9/11 era, when more and more responsibility, including decisions with strategic consequences, is being exercised by more junior officers in theater, the defense department continues to maintain a top-heavy hierarchy that more reflects 20th-century protocols than 21st-century realities.

For example, unlike most other commands, four-star service component headquarters remain in Europe, long after the end of the Cold War and long after the vast majority of their fighting forces have departed.

We need to create a system of fewer, flatter and more agile and responsive structures, where reductions in rank at the top create a virtuous cascading downward and outward. In addition to the number of senior positions, there is also the question of their allocation and whether our distribution of rank by geography or function reflects the mission – missions and realities our military faces today.

Therefore, I am directing a freeze at FY '10 levels on the number of senior civilian – of civilian senior executive, general and flag-officer and PAS positions. Furthermore, a senior task force will assess the number and location of senior positions, be they old or new vintage, as well as the overhead and accoutrements that go with them. I expect the results of this effort by November 1st.

At a minimum, I expect this effort to recommend cutting at least 50 general and flag-officer positions and 150 senior civilian executive positions over the next two years.

Secretary Gates laid out the framework to begin to fix this problem. Now, President Obama needs to tell Secretary Panetta to reverse his position and get on with it.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.