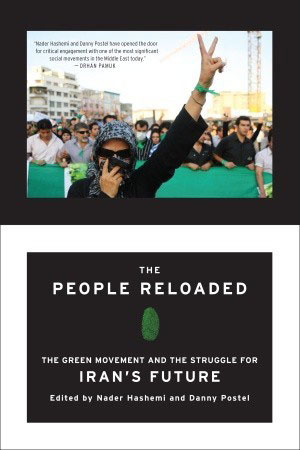

The People Reloaded: The Green Movement and the Struggle for Iran’s Future

edited by Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel (Brooklyn, New York: Melville House), 2010; $18.95.

In the euphoria over the “Arab Spring”, which has brought revolutions to the doorsteps of autocratic regimes that only last year seemed unflappable in their resolve to keep the aspirations of their peoples suppressed, it becomes imperative to recall that the first sustained signs of change in west Asia in recent years appeared in Iran. The Arab world seemed so firmly in the grip of monarchs and dictators, many of them bolstered by the United States (US), which has been in the business of exporting the rhetoric of electoral democracy to the world but has feared reform and revolution at every turn, that no one expected the people to take to the streets in millions. And how people have stormed the streets, facing police barricades, braving tear gas and baton charges – and not just in the Arab world! The Arab spring turned into a long summer of discontent, as signs of protest began to appear in other parts of the world, in Athens, Rome, Madrid, Tel Aviv, and elsewhere. As these lines are being written, the Occupy Wall Street movement has even brought dissenters and rebels to the fore in the US, where politics for far too long has been reduced to an exercise of choosing between Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Yet, all this was anticipated in Iran’s dramatic political upheaval in June 2009, the outcome of which, perhaps contrary to received opinion, is far from settled.

Road to Revolution

Though nearly everything in Iran is marked by the watershed events of 1979 that led to the ouster of the Shah and the assumption of power by the Ayatollahs, it is possible that some years from now the phrase, “after the revolution”, will resonate with an altogether different meaning. The burden of the present collection of essays, The People Reloaded, which brings together the reflections of some 50 scholars, activists, and observers of contemporary Iranian society, is to suggest that we may be in the midst of another momentous upheaval in Iran’s 30 years after the revolution which replaced the dictatorship of the Shah with the rule of a theocratic elite. Some of the contributors take a long-term view of Iranians’ “bloody and painful march towards democracy” (p 27), commencing with the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 and the coup, engineered by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and British military intelligence, of 1953, which led to the deposition of the nationalist hero Mohammed Mossadegh; others hearken back to the Shah’s despotism and the political skill with which Ayatollah Khomeini and his supporters orchestrated his removal; and yet others set their sights resolutely on the mammoth protests against the “stolen election” of 2009. But all the contributors are clearly animated by one central question, aptly reflected in the book’s subtitle, “The Green Movement and the Struggle for Iran’s Future”: how might political action in Iran continue to be steered in directions that would help to secure a future for the country’s citizens that allows for the fulfilment of legitimate political aspirations, the free pursuit of one’s livelihood, economic security, and some commonly agreed upon conception of human dignity?

“Iran”, writes Ervand Abrahamian with precision and elegance, “has a healthy respect for crowds – and for good reason” (p 60). It is the crowds that started gathering in Tehran, Isfahan, Shiraz and other provincial towns in June 2009, most particularly, the million or two or more people who converged on Tehran’s Azadi (Freedom) Square on the 15th in a silent rally, as the 10th presidential election since the 1979 revolution came to an end, that are the subject of this book. As the election results were announced, unambiguously affirming the victory of the incumbent, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran appeared to be engulfed by huge waves of disbelief. A host of pre-election polls suggested that Ahmadinejad and his closest competitor, the reformist Mir Hossein Mousavi, were neck-to-neck; yet, Ahmadinejad would be declared the winner with 64% of the vote. Mousavi, it was announced, had been unable even to carry his hometown of Tabriz; meanwhile, another candidate, Mehdi Karroubi, apparently had more people campaigning than voting for him. Reports of fraud came streaming in – an extra 14.5 million ballots had been printed, and could not be accounted for; or, to take another example, voting had not even been completed in some districts when Ahmadinejad was declared the victor on state-owned television. The complaints lodged with the Election Commission would have a predictable outcome: on investigation, the interior ministry dismissed allegations of rigging and fraud as baseless, and went on to issue advisories urging people to accept the electoral results and desist from protests.

Over a few days, notwithstanding supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini’s admonitions that protestors, characterised by Ahmadinejad as “specks of dirt”, would face the wrath of the law, the crowds surged in size. Tehran’s own conservative mayor estimated that three million people had gathered in Tehran on 15 June to register their dissent – one of the largest gatherings of people, bereft of arms and intent on non-violent resistance, in recent history anywhere in the world. If repression is generally the only language in which the modern nation state trades, then Iran’s response cannot be viewed as entirely surprising. On 20 June the 27-year-old Neda Aghan-Soltan, a philosophy student and budding musician with no previous history of involvement in politics, was shot dead by a member of the Basij (government) militia as she approached the site of the protest. Three amateur videos of her death went viral: within days, millions around the world had viewed them and Neda had become, at least in the west, the supreme icon of resistance to theocratic despotism. As criticism of the government mounted, the full machinery of state repression was brought crashing down upon the dissenters. Before the end of the month, the protestors had largely dispersed. The state might have imagined that it had broken the backbone of the movement, and dulled the protestors into abject submission with beatings, police firings, and targeted assassinations of dissenters; yet, less than two years later, Iran would again be rocked by a series of demonstrations over the course of a month in February and March 2011.

Sizeable Female Presence

What, then, is the Green Movement, and what are some of the strands of Iran’s complex history and culture that have been interwoven into the nation’s contemporary politics? There remain differences of opinion among the volume’s contributors on the question of the movement’s demography: while the American sociologist Charles Kurzman argues that the less educated in Iran have repeatedly shown themselves to be more supportive of Ahmadinejad (p 17), the Iranian blogger and writer Nasrin Alavi is among those who soundly reject the argument that the movement drew its support largely from educated urban elites. The student leaders, Alavi avers, “are not the children of affluent citizens of north Tehran, but instead come from provincial working-class families or are the children of rural schoolteachers and clerks”; indeed, she goes so far as to say that “these future leaders of Iran hail from the very heartland of Ahmadinejad’s purported support base” (p 211).

What is indisputably true is that those under 30 have predominated among the dissenters, and that it is among the ranks of the young that unemployment rates are the highest – but in these respects the protests in Iran would not appear to be at all atypical. What is far more noteworthy, particularly in view of images about the Muslim world that freely circulate in the west and one suspects in some measure in other parts of the non-Muslim world, is, as a number of contributors point out, “the sizeable female presence in the Iranian Green Movement” (p 37); indeed, if the eminent scholar of contemporary Iranian society, Hamid Dabashi is to be believed, “the most well-known aspect of these anti-Ahmadinejad demonstrations is that women visibly outnumber men”(p 23).

Contrary to the overwhelming impression about the docility of Muslim women that has been formed in much of the world, Iranian women have played a not inconsiderable role in the political life of the nation. The “Million Signatures Campaign” (2006), which has resulted in the arrest of some of Iran’s most respected feminists and human rights campaigners, sought to put men on notice that Iranian women sought complete equality under the law; and the “Stop Stoning Forever” campaign has sought alterations to Iran’s Islamic Penal Code, the greatest burden of which has, not surprisingly, fallen upon women.

If the 1979 revolution imposed constraints on women, it also emboldened those who came from traditional families and who were reluctant to enter higher education in the days of the Shah to step into the public sphere once the revolution mandated segregation by sexes. This may partly explain why, even if a little more than 12% of Iran’s labour force is comprised of women (p 38),

women are nearly two-thirds of all entering university students.

Green and Gandhian

The prominence of women at demonstrations in Iran may offer as well some cues on the remarkably non-violent nature of the protests. The dissident cleric Mohsen Kavidar, asked to explain the most salient aspects of the Green Movement, noted that it is “peaceful and against violence” (p 113), and the Toronto-based Iranian philosopher, RaminJehanbegloo, is certain that Iran in 2009 experienced a “Gandhian moment” (p 19). Mousavi’s advisor, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, writing in the Guardian (London) in the thick of the struggle, may have put the matter more accurately when he said of his leader: “Previously, he was revolutionary, because everyone inside the system was a revolutionary. But now he’s a reformer. Now he knows Gandhi – before he knew only Che Guevara. If we gain power through aggression we would have to keep it through aggression. That is why we’re having a green revolution, defined by peace and democracy” (“I Speak for Mousavi. And Iran”, 19 June 2009).

The colour green has long been associated with Islam, and Kavidar suggests that in flaunting green ribbons and banners, the demonstrators may even have sought to convey the idea that they were not prepared to relinquish their Islam to the Ayatollahs and other official purveyors of the religion. To be “Green” and “Gandhian”, however, means much more than abstention from violence and adherence to non-violent strategies of resistance to oppression. It may be too much to expect that non-violence should become for everyone, as it did for Gandhi, the very law of our existence, an unimpeachable and incontrovertible guide to everyday conduct; nor would it reasonable to suppose that everyone should accede to Gandhi’s firmly held belief that to hold to the law of non-violence entails the transformation of one’s whole life such that one might live it with the full awareness of ecological plurality and attentiveness to every little detail.

Nevertheless, one has the feeling that the characterisation of the “Green Movement” as Gandhian has received insufficient critical analysis, just as on occasion some of the contributors seem to want to embrace, rather too easily, slick terms such as “cultural Jiu-Jitsu” or “Green Tsunami” or facile comparisons with the American Civil Rights Movement to highlight the significance of Iran’s own great movement of dissent.

Shortcomings in Volume

A more intensely political reading of what has transpired in Iran over the last few years may perhaps suggest other shortcomings in the volume to some readers. Iran has been looking down the barrel of a gun for decades: though the profoundly democratic aspirations of the volume’s contributors need not be doubted, few of them choose to consider how the relentless assault on Iran’s sovereignty, spearheaded since the revolution of 1979 by the US, has played its part in shaping the world view of the so-called “hardliners”.

Similarly, many of the contributors underestimate the intense resentment that persists against Britain in many sectors of Iran’s society, and in general, the history of anti-colonial sentiment and resistance receives little attention in this volume. These deficiencies may, in the last analysis, be overlooked, since the contributions essayed in this volume offer nuanced and perceptive insights into the remarkable display of people’s power in Iran. Those who have lavished their attention on the Arab Spring, or, more lately, on the Occupy Wall Street movement as it unravels across the US, Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere, would do well to turn their gaze back on Azadi Square in Tehran, June 2009. The democracies in the global north have long thought that it is their prerogative to lead the way; but, if there is at all a grave inference to be drawn from the movement in Iran documented and dissected in The People Reloaded, it may be that the vanguard of resistance to oppression will be found in all those places where it has been least expected. For this reason, if for none other, Iran’s Green Movement augurs a new phase in the global politics of resistance.