US anthropologists Robert Walker and Kim Hill recently published an article in Science to argue that governments are violating their responsibility to “protect” isolated tribes if they eschew contact with them. Their argument threatens to undercut advances in indigenous rights that have painstakingly evolved over a generation.

Walker and Hill show how first contacts with isolated Amazon tribes result in massive population decline, but they nevertheless go on to claim it’s “a violation of governmental responsibility” for governments to “refuse authorized, well-planned contacts.” The magazine, which often employs the tropes of the “brutal savage” in its portrayal of tribal peoples, declined to print the critical comments that the anthropologists’ article elicited.

Brazil used to have the policy that Walker and Hill suggest: Its government instigated contacts with indigenous people in order to “open up” the Amazon and exploit its resources between the 1960s and 1980s. It wanted to “pacify” the tribes so they would stop resisting the theft of their lands. Antonio Cotrim, one of the fieldworkers, ended up saying he could no longer stomach being a gravedigger for the indigenous people he had befriended. Apoena Meirelles, one of the most experienced experts on indigenous peoples, said the tribes soon began “the first steps down the long road to misery, hunger and … prostitution.” Meirelles added, “I would rather die fighting … in defense of their lands and their right to live, than see them reduced to beggars tomorrow.”

From “Pacification” to Protection

By the late 1980s, the department charged with Brazilian indigenous affairs, FUNAI, had shifted its policy away from “pacification” and started trying to stop the invasion of indigenous territories in the first place.

Walker and Hill, however, want to turn the clock back. They claim that a “well-organized plan” and access to medical staff are all it takes for contacts to be success stories. But it’s not true: The Brazilian authorities had plans aplenty when indigenous people were dying in droves and there are numerous cases where medical personnel couldn’t, and still can’t, prevent deaths.

Sydney Possuelo, a former FUNAI head, who organized dozens of contact expeditions over more than 40 years, said that upon first making contact with the Arara indigenous people, “I believed it’d be possible to make contact with no pain or deaths; I organized one of the best equipped fronts that FUNAI ever had. I prepared everything … I set up a system with doctors and nurses. I stocked with medicines to combat the epidemics which always follow. I had vehicles, a helicopter, radios and experienced personnel. ‘I won’t let a single Indian die,’ I thought. And the contact came, the diseases arrived, the Indians died.”

Walker and Hill take a stab at justifying their position with the perverse claim that it’s unlikely that isolated tribes are “viable.” According to them, outside disease “compounded by demographic variability and inbreeding” makes these tribes’ disappearance “very probable in the near future.” Hill goes further in a separate paper in which he writes, “Almost certainly many isolated groups went extinct in the 20th century without ever making contact.” This is odd: In reality, there are plenty of uncontacted tribes – many more than double the number the authors claim – and those whose land hasn’t already been invaded invariably appear robust and healthy. There’s no evidence that many have died out without outside involvement.

Uncontacted indigenous people in Amazonia make their views clear. (Photo: © Gleison Miranda/FUNAI 2008)Tribes are at grave risk, but that’s from disease and violence resulting from the invasion of their territory. When left alone, they seem as “viable” as anyone.

Uncontacted indigenous people in Amazonia make their views clear. (Photo: © Gleison Miranda/FUNAI 2008)Tribes are at grave risk, but that’s from disease and violence resulting from the invasion of their territory. When left alone, they seem as “viable” as anyone.

The Myth of Population Rebound

The anthropologists further claim, “soon after peaceful contact … surviving indigenous populations rebound quickly from population crashes.” The key word here is “surviving.” Tribes who do not survive contact obviously do not rebound at all. There are several known instances of remnant tribes reduced by contact to a dozen or fewer people, and there are doubtless countless other unrecorded cases of tribes being killed altogether by disease and violence. There are also many examples that directly contradict the anthropologists, in which the population has remained far below pre-contact estimates for generations, in spite of the availability of Western medicine. Aboriginals in Australia, for example, still number only about half pre-contact estimates.

The anthropologists’ concept of “population crash,” which they appear to mitigate with the subsequent concept of “rebound,” is of course a euphemism for the avoidable suffering and dying of millions of indigenous people since Columbus.

When the surviving population grows, for example, in North America, their problems with miserable health, early death, alcohol and substance abuse, suicide and so on hardly seem persuasive as an endorsement of our own particular version of human society.

Nevertheless, Walker and Hill think it “unlikely” that tribes “would choose isolation if they had full information (i.e., if they were aware that contact would not lead to massacre and enslavement).” This superhuman (inhuman?) prescience is among their least defensible claims: The “full information” is not massacre and slavery. The main killer of newly contacted tribes is disease, followed by violence, and then land theft resulting in catastrophic social disintegration. This is glaringly and tragically obvious in many Native American reservations as well as, for example, with the Guarani in Brazil where the youngest recorded suicide – so far – was a 9-year-old girl.

What tribe would abandon isolation if it could first study Pine Ridge or the Guarani, and if it knew that many of its children would die as a result? There are plenty of contacted tribes that do know what happens and respond by striving to protect isolated relatives from contact. A Kaxinawá indigenous person, Valmir, recently reported that there are several uncontacted groups nearby: “We’re protecting their land and staying away … so they can live comfortably.”

An Awá man, Wamaxua, said, “When I lived in the forest, I had a good life. Now, if I meet one of the uncontacted … I’ll say, ‘Don’t leave … there’s nothing in the outside for you.'” Uncontacted Awá are now not only protected by their Awá relatives, but also by Guajajara indigenous people.

The fact that there are cases where contacted indigenous people have subsequently retreated into greater isolation gives further lie to Walker and Hill’s thesis. The real facts lead to only one humane policy: to stop the invasion of tribal land, not to accelerate it with contact expeditions.

Tens of billions of dollars are sucked from indigenous territory every year, but the budget of Brazil’s indigenous agency is minuscule, with much of it wasted on bureaucracy. Indigenous organizations, as well as FUNAI’s best fieldworkers, are starved of the funds needed to protect the land simply because many in the controlling establishment want to profit from its theft.

That same establishment is aided and abetted by the international corporations, banks, developers and conservation agencies – by “us” in other words – all grabbing a slice of a cake that isn’t ours in the first place.

Walker and Hill’s hypothesis plays straight into the hands of those who want to steal indigenous lands. The duo also fails to grasp how human rights work: All major advances, from anti-slavery to anti-apartheid, from gender equality to racial equality, have succeeded because they challenged and began to overturn a deeply entrenched status quo.

Two hundred years ago, progressives faced a choice: accept slavery as inevitable but try to get slaves treated better, or actually fight to end it. It’s the same here: whether consciously to bring uncontacted tribes into the industrialized world – like it or not – just hoping to ensure not too many die in the process, or whether to help them protect their ancestral land, which is supposed to be theirs anyway, and allow them to choose their own futures.

Jakarewyj Awá (left), contacted in December 2014, is now critically ill in spite of the staffed medical post nearby. (Photo: © Survival International, 2015)

Jakarewyj Awá (left), contacted in December 2014, is now critically ill in spite of the staffed medical post nearby. (Photo: © Survival International, 2015)

The Importance of Land Rights

Indigenous rights have moved on since 50 years ago, when ranchers could get away with a court plea that they had no idea it was wrong to kill indigenous people. The most important legal principle now is that nothing should happen on tribal land without the free, prior and informed consent of its indigenous owners. Incursions onto the land of uncontacted tribes violate this. Walker and Hill, though, are clearly unconcerned with such legal niceties; their article makes a single, fleeting reference to “native rights” but doesn’t say what they are, or even mention the essential key to tribal survival – land rights.

They may argue that the laws are barely applied, but that’s no reason to abandon them. It’s time for industrialized society to start upholding UN norms and corporate social responsibility policies. It’s time for corporations to stop investing in schemes that don’t have the proper consent of those whose lands they wreck, especially when they belong to the most vulnerable peoples on the planet.

Besides, there are plenty of cases when legal enforcement has been successful: Brazil recently evicted loggers from an Awá indigenous territory; gold miners have frequently been thrown off Yanomami land; Mobil was prevented from working in the Mashco Piro’s forests in Peru, and so on. The land of uncontacted indigenous people is being protected in some places, at least for now.

Stopping the theft of indigenous land is not just the key to stopping the annihilation of South America’s indigenous peoples; it’s also crucial in protecting Amazonia itself. The easiest and by far the cheapest way to save rainforests is to ensure as much of it as possible remains in indigenous hands.

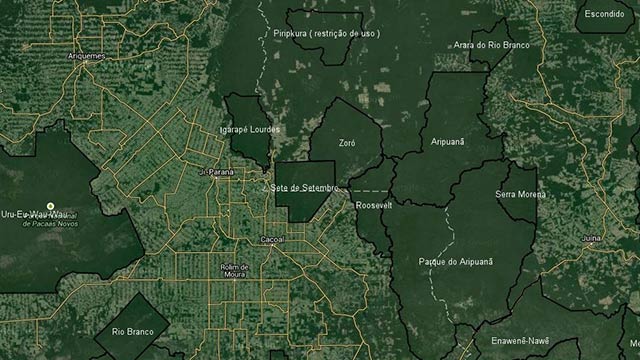

Satellite pictures show Amazonian rainforests protected by indigenous territories. (Image: © Google Earth)

Satellite pictures show Amazonian rainforests protected by indigenous territories. (Image: © Google Earth)

Uncontacted indigenous people would do well to be wary of those wanting to study them, and particularly wary of any anthropologists not known for their stalwart defense of indigenous rights.

In 1978, Kim Hill was a young US federal employee in the Peace Corps, recently arrived in Paraguay, a country that had already been in the grip of military dictatorship for a quarter century. He denied that the Aché indigenous people had suffered genocide, in spite of experts having said so for years. It was all, he glibly pronounced, “more complex.” However arcane Hill’s reasoning, his genocide denial undoubtedly suited the United States: It enabled the US to continue propping up Paraguay’s dictator. USAID could now sidestep President Carter’s new law, which prevented the United States from funding governments guilty of gross human violations. With Aché genocide denied by US “experts,” US aid and the Peace Corps could carry on, as did the murderous regime.

Hill is right that the full story is always complex, but that mustn’t mean turning reality on its head, particularly when the destruction of entire peoples is at stake.

The survival of tribal peoples depends on their land being protected. This is particularly vital for those who choose to avoid contact, but also applies to those who seek it (and no serious commentator is saying they must be prohibited from doing so).

It’s only a few years since uncontacted peoples were called a hoax. Now their existence is undeniable. We obviously know things they don’t, but they know things we don’t. They represent humankind’s greatest diversity and proclaim the universal human genius for shaping the environment sympathetically to improve life. They are peoples in their own right.

It’s time to stand in resistance against those who just can’t abide that there are some who choose a different path to ours, who don’t subscribe to our values and who don’t make us richer unless we steal their land.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.